March 13, 2020

As Illinois voters head to the polls for next week’s Presidential primary, this blog post looks at another major choice that will be on the general election ballot in November: whether to replace the State’s flat-rate income tax with a graduated rate structure. The post reviews the proposed new tax rates and examines who will pay more under the new plan and how much revenue it is expected to raise.

Illinois has had a flat rate—currently 4.95% for individuals—since the income tax was instituted in 1969. The Illinois Constitution mandates that any income tax be imposed at a single rate for all individual taxpayers, regardless of their income level. The Constitution also dictates a single corporate tax rate that may not be more than 60% higher than the individual rate.

Last year, at the urging of Governor J.B. Pritzker, the General Assembly approved a constitutional amendment to go before voters in November 2020 that removes the flat-tax requirement. The amendment also modifies the corporate rate limit by requiring that the highest corporate rate not exceed the highest individual rate by more than 60%.

The legislature also approved a new graduated rate structure for individual income taxes that will take effect on January 1, 2021 if the constitutional amendment passes. Of the 41 states with general income taxes, Illinois is now one of only nine with a flat tax. However, the rate structures in the 32 states with graduated rates vary widely, which will be discussed in detail in a future post.

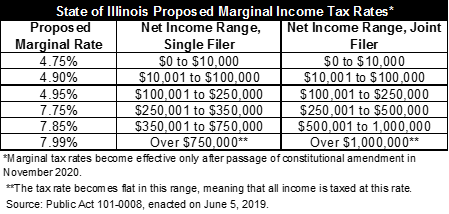

The following table shows the new Illinois individual income tax rates passed by the legislature and enacted on June 5, 2019 in Public Act 101-0008.

The enacted graduated rates are similar to those proposed in March of last year by Governor Pritzker. The biggest difference is an increase in the top tax rate to 7.99% from 7.95% in the Governor’s initial proposal. The legislation also raised the flat corporate rate to 7.99% from 7.95% in the Governor’s proposal and the current 7.0%. (Illinois corporations also pay a Personal Property Replacement Tax of 2.5%, which is effectively an additional tax on corporate income.)

For those at higher income levels, the enacted tax plan includes a different rate structure for single tax filers and married couples. This change was intended to address criticism about a significant marriage penalty related to the Governor’s initially proposed rate structure, which did not distinguish between single and joint filers. A marriage penalty exists when joint filers have a higher combined tax burden than they would have had if they had remained single.

For single taxpayers with up to $750,000 of net income and joint filers with up to $1 million, the enacted plan uses a tax bracket structure applied in the same way as federal income taxes and most other states with graduated tax rates. The first dollars earned by all taxpayers are taxed at the lowest rates. Taxpayers earning more are subject to higher rates, but only on their net income above the threshold amounts for each bracket.

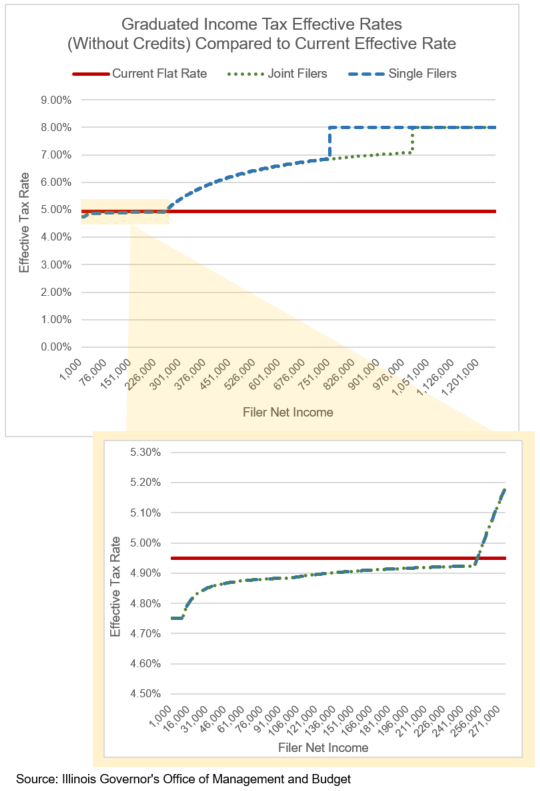

The tax rate applied to a filer’s last dollar of income is called the marginal rate. The ratio of the total tax paid to net income is called the effective rate. In a flat-tax system, marginal and effective rates are the same. In a typical graduated tax system, except in the lowest income bracket, effective rates are below marginal rates due to lower marginal rates on the first dollars of income.

Under the Illinois plan, filers with up to $100,000 would see slightly lower marginal rates of 4.75% or 4.90%, compared with the current 4.95%. Filers with $100,001 to $250,000 would see no change in their marginal rate. Single filers with $250,001 to $750,000 and joint filers with $250,001 to $1 million would face higher marginal rates of up to 7.85%. However, filers with less than about $253,000 would see no increase in their effective rates because of the lower rates paid on lower brackets of income. The effective tax rate is 6.86% for single filers with $750,000 and 7.09% for joint filers with $1 million.

At the highest income levels, Illinois’ enacted tax plan, like the Governor’s initial plan, deviates from most states’ graduated tax structures. For single taxpayers with more than $750,000 of net income and joint filers with more than $1 million, the tax rate becomes a flat 7.99%. That means that all income is taxed at the same rate, so the wealthiest taxpayers do not benefit from lower rates applied to their first dollars of income. Graduated income taxes that become flat at the top are rare, but not unprecedented, among other states. According to the Tax Foundation, three other states—Connecticut, Nebraska and New York—have similar structures, which are known as recapture provisions.

The next chart, based on information provided by the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB), compares Illinois’ current flat individual income tax rate with effective tax rates under the enacted plan. The calculations do not account for exemptions, deductions and tax credits, which would result in lower effective rates for most filers.

As shown above, the recapture provision results in a spike in effective tax rates. A single filer’s effective rate jumps from 6.86% to 7.99% when net income increases from $750,000 to $750,001; the tax bill rises from $51,460 to $60,005. Joint filers see an increase in effective rates from 7.09% to 7.99% when their income rises from $1 million to $1,000,001; their tax bills increase from $70,935 to $79,980.

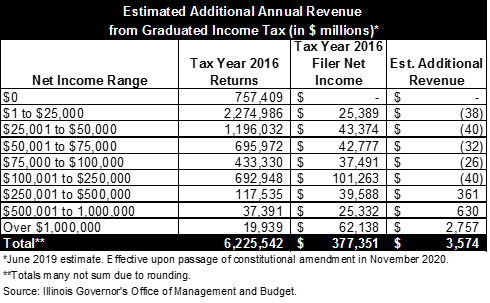

According to GOMB’s figures, which are based on tax year 2016 returns, 85.0% of the State’s 6.2 million tax filers will see lower tax bills, while 2.8% will see higher bills. The remaining 12.2% do not owe any taxes. The 5.3 million filers with lower bills will have combined savings of $176 million, an average of $33 per filer. The 174,865 filers with higher bills will see a combined increase of $3.7 billion, an average of $21,434 per filer. Most of the increase is expected to be paid by the 19,939 taxpayers with more than $1 million of net income, who represent 0.3% of total filers. Their tax bills will increase by $2.8 billion, or $138,272 per filer.

These calculations do not account for tax credits in the new plan that could reduce taxpayers’ bills. Public Act 101-0008 increases the property tax credit to 6% of property taxes paid per year from 5% and provides a child tax credit of up to $100 per year for single filers with under $80,000 and joint filers with less than $100,000.

In all, GOMB estimates additional individual income tax revenue due to the graduated tax plan (net of amounts set aside for tax refunds) of about $3.6 billion per year. As explained in a previous blog post, this result assumes that the relatively rapid growth in high-income households in the years following the Great Recession continues through 2020. However, the calculation also assumes no income growth in 2021 from the previous year to make the estimate more conservative. GOMB’s estimate has not been updated since June 2019 and does not reflect any income growth in 2022.

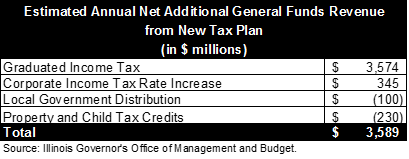

The next table shows GOMB’s estimate of total annual revenues available for general operations, after adding proceeds from the increased corporate income tax rate and deducting the costs of tax credits and distributions to local governments. As discussed here, the enacted plan reduced the local government share to $100 million from $237 million in Governor Pritzker’s initial proposal.

The Governor’s proposed budget for FY2021 relies on $1.4 billion from the new tax plan. If approved by voters, the plan would take effect midway through the fiscal year, which begins on July 1, 2020. The $1.4 billion estimate is net of a $100 million supplemental contribution to the State’s massively underfunded retirement systems. The Governor’s budget also recommends that $200 million of the plan’s proceeds in FY2022 and future years be used to shore up the pension funds.