January 24, 2020

More than 50 years after Illinois began taxing residents’ income, voters in 2020 will decide whether the structure of the income tax should undergo a major change. The issue is highly controversial, and the decision will have a long-lasting impact on the State’s finances.

Since Illinois’ income tax was adopted in 1969, the State has had a flat income tax. Although tax rates have varied over the years, every taxpayer has paid the same rate, which is currently 4.95%. That could change due to a proposed constitutional amendment that will appear on the November 2020 ballot. For the first time in the State’s history, the measure would permit a graduated tax structure in which higher tax rates are applied at higher income levels.

The graduated tax amendment is a priority for Governor J.B. Pritzker and is expected to be a focus of policy debate in Illinois this year. The Civic Federation plans to publish a series of blog posts related to the graduated tax proposal, beginning with this post on the existing income tax. Of the 41 states with a general income tax, Illinois is one of only nine with a flat tax.[1] Illinois’ income tax was difficult to establish and has not been easy to change.

Early Efforts to Tax Income[2]

Until the Great Depression, Illinois relied on a statewide property tax for most of its revenue. The Illinois Constitution of 1870 contained a revenue article that authorized taxes on four categories: property, privileges, franchises and certain occupations. It also required that taxes on each category had to be uniform.[3]

A new constitution, designed to replace the 1870 governing document, was presented to voters in 1922. To address the State’s growing revenue problems, the proposed revision included a provision for an income tax. The provision specified that the income tax rate could be graduated, but the highest rate could never exceed three times the lowest rate. The revised constitution was decisively rejected by voters for numerous reasons, including objections to the revenue proposal from both ends of the political spectrum.

The 1929 stock market crash and subsequent economic devastation led to broader support for income taxes. Illinois’ property tax system virtually collapsed during the Depression, causing the General Assembly to abolish the statewide property tax and reserve its use for support of local governments. As an alternative State revenue source, the legislature in 1932 approved the creation of an income tax with graduated rates. The tax had six brackets, with rates ranging from 1.0% on the first $1,000 of income to 6.0% on income over $25,000.

However, the new tax was immediately struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court. The justices held in Bachrach v. Nelson that income must be considered as property and thus the new law’s graduated rates violated the uniformity provision in the Constitution. The high court also held that the Constitution prohibited the legislature from levying any new types of tax. The General Assembly was only allowed to add to the list of occupations, franchises and privileges listed in the Constitution’s revenue article.

The Bachrach decision effectively blocked moves to levy an income tax for more than three decades. The General Assembly turned to the sales tax, approved in 1933, as State’s main revenue source. This tax was technically structured as a retailer’s occupation tax, a constitutionally permissible tax on occupations.

Establishment of a Flat Tax

By the 1960s, consensus had begun to build for an overhaul of Illinois’ fiscal system to provide an adequate financial base. Pressure was increasing for more State aid to schools and local governments due to rising local property tax rates. In 1967 the legislature approved increases in State and local sales tax rates that raised the combined rate to among the highest in the nation.

Facing a $1 billion budget deficit in fiscal year 1970, then-Governor Richard Ogilvie in April 1969 proposed a 4.0% flat income tax on individuals and corporations. With lukewarm support from his own party, the Republican Governor lowered the proposed rate on individuals to 2.5% to win support from Democratic legislators. The tax enacted on July 1, 1969 has been blamed for Governor Ogilvie’s re-election loss in 1972 and for Republican loss of control of the State Senate in 1970.

The Illinois Income Tax Act was immediately denounced as unconstitutional, and the Illinois Supreme Court was asked to determine the statute’s validity. In a surprising decision on July 25, 1969, the State’s high court overturned Bachrach and ruled that the income tax could stand. The decision in Thorpe v. Mahin held that the income tax was not a property tax; that the legislature was not limited to levying taxes on occupations, privileges, franchises and property; and that uniformity did not prohibit distinctions among reasonable classes of taxpayers, such as individuals and corporations.

The Income Tax Act and subsequent Supreme Court ruling came after voters approved the call for a constitutional convention in November 1968 and before the convention began in December 1969. One of the main issues on the convention’s agenda was the imposition of an income tax.[4] After the Thorpe decision, there was little consideration of prohibiting income taxation in the new constitution. Business organizations favored limits on corporate taxes, while many education and labor groups sought graduated rates. However, the overriding concern was preserving the status quo by winning voters’ support for a governing document that enshrined the previously enacted income tax.

The 1970 Constitution, approved by voters in December 1970, authorized a non-graduated income tax with one rate for individuals and one rate for corporations. Although no specific rate limit was specified, the document required that the ratio between corporate and individual tax rates could not exceed eight to five; in other words, corporate rates could be at most 60% higher than individual rates. That provision reflected the ratio in the Income Tax Act: 2.5% for individuals and 4.0% for corporations.

Modifying the Illinois Income Tax

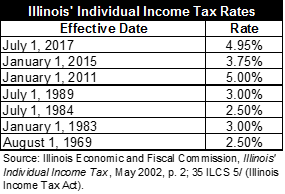

The initial individual tax rate of 2.5% remained unchanged for 14 years, and many of the subsequent rate changes were temporary. The following table shows the history of individual income tax rates from 1969 to the present.

In 1983 the rate was temporarily raised to 3.0% for 18 months before reverting to 2.5% for another five years. The rate was again increased to 3.0% on July 1, 1989. It was scheduled to roll back to 2.5%, but the 3.0% rate became permanent on July 1, 1993 and remained in place through 2010.

The tax rate has been more variable in the past decade. Because the individual income tax is the State’s largest revenue source, recent rate fluctuations have played a large role in Illinois’ financial condition.

Following the Great Recession, the State approved a temporary increase in individual income tax rates to 5.0% midway through fiscal year 2011. Corporate income tax rates, which had increased to 4.8% in 1989, were raised to 7.0%.[5] After four years at temporarily increased rates, the rates automatically declined on January 1, 2015 to 3.75% for individual income taxes and 5.25% for corporate income taxes.

The rate drop triggered a prolonged budget impasse, as a Republican Governor refused to raise income tax rates without pro-business policy changes that were blocked by a legislature under the control of Democrats. After two years without a complete budget, the deadlock was broken in July 2017, when the General Assembly overrode the Governor’s veto and raised the individual rate to 4.95%. Corporate rates were restored to 7.0%.

The individual tax rate is applied to Illinois net income. The starting point is federal adjusted gross income, which is modified in several ways and then reduced by specific exemption amounts to arrive at net income. The personal exemption allowance has increased from $1,000 in 1969 to $2,275 currently for each taxpayer, spouse and dependent. Additional exemptions of $1,000 are available for taxpayers who are over 65 or blind. However, taxpayers with federal adjusted gross income over $500,000 for joint filers and $250,000 for single filers have not been eligible for exemption allowances since income tax rates were increased in July 2017.

When the personal exemption was increased from $2,000 to $2,050 for tax year 2012, the amount was indexed for inflation for the next four years. That law sunset in 2017 and the exemption rolled back to $2,000. A 2018 law reinstated the exemption at $2,050 plus inflation since 2011, but the exemption is scheduled to decline to $1,000 after tax year 2023.

[1] Of the 32 states with graduated income taxes, eleven have very low top brackets, meaning that the highest tax rate applies at a relatively low income level and the resulting tax structure is only marginally progressive. This issue will be discussed in more detail in a future post.

[2] Historical information summarized in this post is based largely on Janet Cornelius, Constitution Making in Illinois, 1818-1970 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972), pp. 85-138; Roland Calia, The Institutional Origins of Social Policy in the American States, 1996, University of Chicago, PhD dissertation, pp. 102-125; and Joyce Fishbane and Glenn Fisher, Politics of the Purse: Revenue and Finance in the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974).

[3] The 1870 Constitution required that “every person and corporation shall pay a tax in proportion to the value of his, her or its property,” which was interpreted to mean that property taxes be general and uniform, rather than specific taxes levied on specific types of property. Joyce Fishbane and Glenn Fisher, Politics of the Purse: Revenue and Finance in the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974), p. 6.

[4] In 1966 Illinois voters rejected a constitutional amendment authorizing a flat income tax rate of up to 5.0% for both individuals and corporations. Income tax proponents hoped a sweeping overhaul of the entire constitution would result in a more favorable outcome.

[5] Corporations also pay a Personal Property Replacement Tax of 2.5%, which is effectively an additional tax on corporate income.