August 18, 2025

by Daniel Vesecky

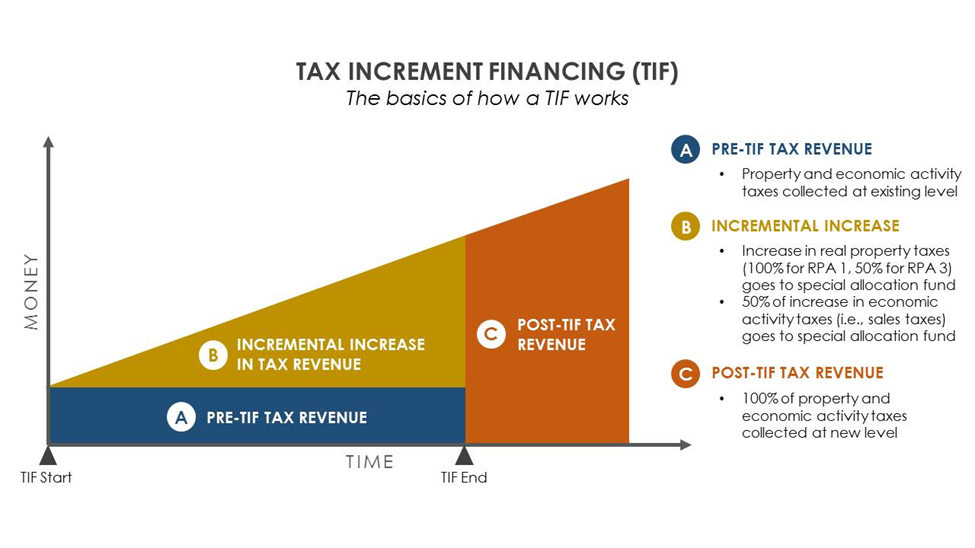

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Districts are a complex, often misunderstood part of Chicago’s tax structure. TIF Districts segment and dedicate a portion of property tax collections within a designated geographic area to fund economic development and capital or infrastructure projects. They do not, as critics often claim, siphon funds away from local governments. Instead, TIF districts limit the taxable value of property, or the tax base, from which local governments can draw their property tax levies, which is the amount of money that governments request in property tax revenue to fund their budgets each year. TIF districts do not directly limit the amount of money for which local governments can levy. Instead, they raise new, previously non-existent tax revenue connected to the growth in taxable property value above the base that occurs during the life of the TIF. TIF revenues make up a large portion of the local property tax system, and the funds they generate support projects that benefit the City of Chicago and its sister agencies, including the Chicago Public Schools (CPS or the “District”). This explainer will examine how TIFs interact with CPS and how the District draws revenue from this obscure revenue source.

There are three ways CPS can get revenue from TIF:

1. TIF Surplus: CPS receives a portion of TIF surplus funds annually declared by the City of Chicago. TIF surplus is excess revenue within a TIF district not needed for development projects or the operation of the TIF district itself. State law mandates that the amount of TIF surplus declared by the City of Chicago is distributed among the local governments, such as CPS, based on their share of total property tax levies.

2. Expiring TIFs: When a TIF district expires, the increased value of taxable property within the TIF district above the frozen base amount is returned to the overall tax base. But first, governments can and usually do levy for the taxable property value of the TIF increment from the expiring district, which is available above otherwise applicable state law tax caps. The revenues generated from applying the government’s tax rate to the TIF increment would previously have gone to the TIF district, but instead go to the government’s coffers to be used for any purpose. This allows governments to increase their property tax revenue without actually increasing overall taxes.

3. Intergovernmental Agreements: The City of Chicago has a process through which it can allocate TIF funding to an infrastructure project proposed by one of its sister agencies, such as the Chicago Public Schools, via intergovernmental agreements created to fund specific projects. CPS frequently receives TIF funding through these intergovernmental agreements, which is typically directed to individual schools for capital projects, such as renovations.

How TIFs Work

TIF districts are created to spur economic development within a specific region of the city. Districts can be as small as a few blocks or as large as over a mile. After a TIF district is designated by the City and approved by the City Council, the taxable value of property (called the equalized assessed value, or EAV) within that geographic area is frozen based on the dollar amount that all property within the area is worth at that time. Thereafter, any incremental growth in the value of property within the TIF district is earmarked specifically for costs associated with redevelopment within the area. By Illinois state statute, TIF districts last for 23 years, with an option to extend their lifespan for an additional 12 years. This renewal must be enacted by the state legislature.

Source: City of Bloomington

One common misconception about TIF districts is the idea that by freezing the taxable value of property, the EAV, TIFs reduce the property tax revenue that other government bodies are receiving. This is not the case. Although TIF districts do halt the growth of the total EAV available to other taxing bodies (the tax base they are drawing revenue from), they do not impact the levy, or the actual dollar amount that governments request from taxpayers. The taxing bodies maintain their normal property tax levies and can increase them annually up to the limit enshrined by state law. (See also our primer on the property tax extension process for more details on these limitations.) That limit is not affected by the number or size of TIFs. Because of this structure, however, while TIFs don’t impact governments’ property tax levies, increasing the number of TIFs effectively increases property tax rates throughout the city. This is because when the EAV within a TIF is frozen, taxing bodies are forced to levy the same or higher taxes based on a smaller citywide amount of EAV.

TIF Surpluses

When a TIF district takes in more revenue than is needed to cover the costs of current or future redevelopment projects, the excess revenue is marked as surplus. Every year, the City of Chicago reviews all TIF districts within the city and identifies those with surpluses. Once the City has determined the total surplus amount, the Cook County Clerk reassigns a portion of the total surplus as revenue for the City and other local taxing districts, in proportion to the most recent distribution of property tax revenues. The City has the sole responsibility to decide how much TIF surplus to declare each year – a process known as a “sweep”. The City has a policy that determines how much unused TIF revenue is swept as TIF surplus. Under the policy, TIF districts with uncommitted funds have 25% of their balance over $750,000 swept, with the sweep increasing to 100% of the balance over $2.5 million. Although the City has the power to change the existing policy, to do so would be to overturn years of precedent.

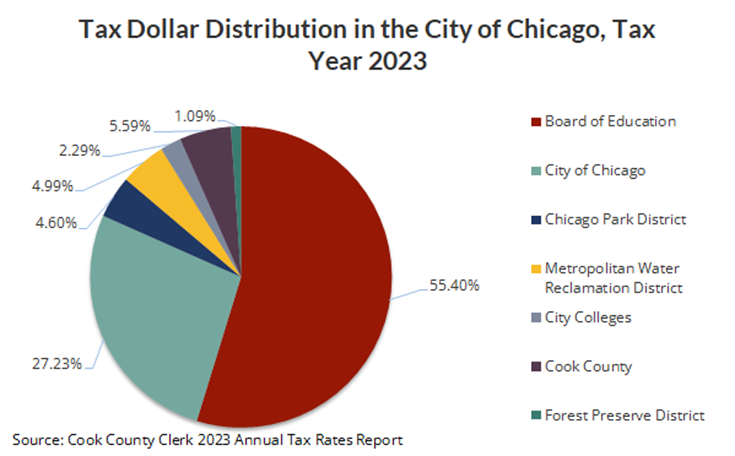

After the size of the surplus is determined by the City of Chicago, TIF revenue is apportioned to all local governments with statutory property tax levy authority. These governments include the City of Chicago, the Chicago Public School District, Cook County, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), the Cook County Forest Preserve District, the Chicago Park District, and the City Colleges of Chicago. Each local government gets a percentage of the surplus based on its share of the normal property tax bill, as shown below. In the 2023 tax year, CPS got 55.4% of the property tax revenue collected in Chicago. Therefore, CPS’ distribution of any TIF surplus funds would be 55.4% for that year.

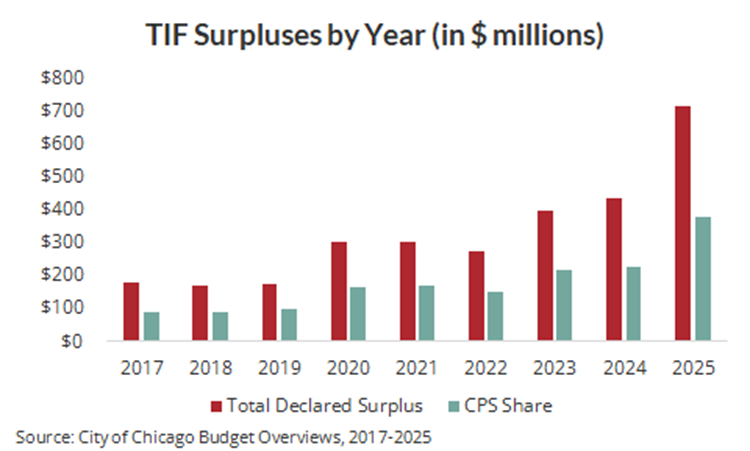

Over the last decade, declared TIF surpluses have steadily grown, reaching a record surplus of $712 million in 2025. Based on its portion of that year’s tax bill, CPS received $379 million of that total TIF surplus amount. Surpluses have grown because overall property tax revenue flowing through the TIF districts has increased, while the number and cost of projects within the districts have remained roughly the same. As a result, more funds remain unspent. Between 2017 and 2025, both total TIF property tax collections and TIF surpluses more than doubled.

In FY2025, CPS had a total budget of $9.9 billion. The $379 million it received from TIF surplus accounted for approximately 4% of its budget, a significant chunk of the District’s total spending.

This TIF sweep and surplus structure has generated concerns that TIF revenue could be used as leverage by the City in other intergovernmental negotiations with CPS. In short, some are worried that the City may hold back TIF surplus funds unless CPS covers a portion of pension costs for non-teaching CPS employees. However, although the City has the power to increase or reduce the overall size of the TIF surplus, the proportion of the surplus distributed to each taxing body is mandated by state law. This means that the City cannot reduce CPS’ TIF surplus without also reducing its own, as well as that of other Chicago-based government agencies. Such a move is especially unlikely at this moment in time, given that the City of Chicago faces its own massive FY2026 budget deficit of over $1 billion.

As the new Board of Education transitions towards being fully elected, rather than appointed by the Mayor, there is growing political interest in disentangling the finances of the City from the finances of the Chicago Public School District. The role TIF surpluses play in the District’s budget presents an impediment to that disentanglement. Although much of CPS’ revenue comes from other governments, such as Illinois through its Evidence-Based Funding Formula and grants from the federal government, TIF surplus revenue is unique in that it is highly variable. Additionally, TIF surpluses are not determined until months after CPS is required to pass its budget. The uncertainty caused by varying TIF surplus sizes often forces the District to devise budgets without knowing exactly how much TIF revenue it will receive in the coming fiscal year. The District often makes uncertain assumptions that can result in unspent money if the surplus is larger than expected or midyear cuts if it is smaller than expected.

Expiring TIF Districts

Another way that CPS gains revenue from TIF districts is when a district expires. When a TIF district reaches the end of its 23-year lifespan (or 35 years if renewed), the equalized assessed value that had been frozen at the TIF’s creation is added back into the pool of property value that is taxable by local governments. This District may then increase its overall property tax levy by applying the existing tax rate to the new base. Importantly, this revenue does not count toward the annual property tax increase limits set by Illinois’ Property Tax Extension Law Limit (PTELL). The law mandates that non-home rule governments, such as Chicago Public Schools, cannot raise property taxes further than the lesser of 5% or the Consumer Price Index for the preceding 12 months. However, by levying on the district’s newly available property value in the year that the TIF expires, CPS can increase its property tax revenue above the statutory limit.

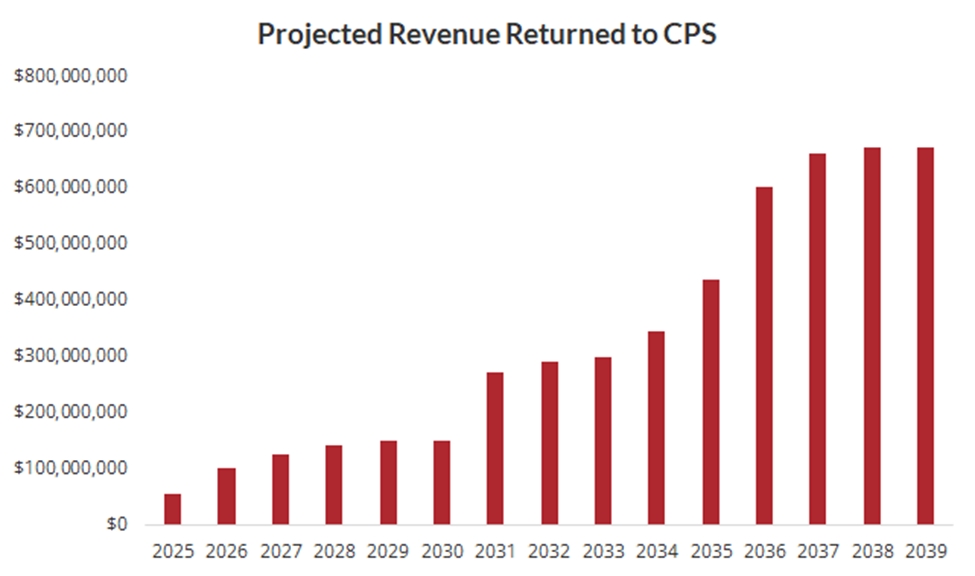

A counterweight to this benefit is that when a TIF district expires, the revenue generated by that TIF is no longer available for surplus in future years. The City of Chicago intends to let many of the existing TIF districts expire to fund its Housing and Economic Development Bond. There are currently 109 active TIF districts within the City of Chicago. Many of those are set to expire in the coming years, which will likely result in increases to CPS’ property tax levy over time, as shown in the chart below. However, because the revenue will shift from TIF districts to CPS and other Chicago local governments, fewer dollars will be available as TIF surplus in future years.

Intergovernmental Agreements

TIF is intended to spur economic development by supporting infrastructure projects, both public and private. More than half of all TIF funds spent on development are spent on public infrastructure projects. Some of these funds are transferred to Chicago’s sister agencies through intergovernmental agreements (IGAs) for infrastructure projects within the boundary of a TIF. The primary beneficiaries of TIF IGAs are the CTA, the Chicago Park District, and CPS.

The amount of TIF funding that CPS receives through IGAs with the City each year is highly variable and depends on the timing of projects and when invoices are paid. Each IGA that CPS and the city make is focused on a single project at an individual school, and CPS’ ability to make IGAs to utilize TIF funding depends on which schools happen to be located within TIFs with available funds. Between 2020 and 2024, Chicago committed roughly $250 million from TIF districts to infrastructure projects proposed by CPS, an average of about $50 million per year. Most of these projects were for the renovation or maintenance of school buildings. Though this money does not go directly into the CPS budget as general operating funds in the way that TIF surplus funds do, these TIF transfers can help supplement the district’s existing capital funding as CPS faces $14 billion backlog of maintenance costs.

This research was supported in part by the Joyce Foundation. The Civic Federation is a nonpartisan, independent research organization, and the views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the Joyce Foundation.