May 30, 2013

As the Illinois General Assembly approached its scheduled adjournment date of May 31, 2013, the State’s pension systems produced new reports estimating the financial impact of proposed pension legislation.

The reports by the retirement systems’ actuaries concern two bills—Senate Bill 1, as amended in the House, and Senate Bill 2404—designed to reduce the State’s pension costs by cutting benefits for employees and retirees. Before the reports were issued, potential State savings from the proposals had been discussed but not documented.

As expected, the actuarial studies showed that SB1 would lead to a far bigger reduction in State pension obligations and greater savings on annual contributions than SB2404. In both cases, however, the numbers were somewhat different than supporters had originally suggested.

The two bills take different approaches to the State’s constitutional guarantee of undiminished pension benefits. House Speaker Michael Madigan’s SB1 is based on the idea that Illinois’ dire financial condition requires that pension benefits be reduced to preserve the State’s five retirement systems while continuing to fund critical State services. Senate President John Cullerton, the sponsor of the union-backed SB2404, argues that a reduction in pension benefits can withstand a legal challenge only if employees and retirees are given something valuable in exchange for forgone benefits.

Supporters of Speaker Madigan’s bill have said it would make a deeper dent in the State’s $96.8 billion unfunded liability (based on the market value of assets) and go further toward stabilizing the State’s finances. Backers of President Cullerton’s SB2404 contend that SB1 is the riskier choice because no savings will be realized if the State enacts pension changes that are found to be unconstitutional.

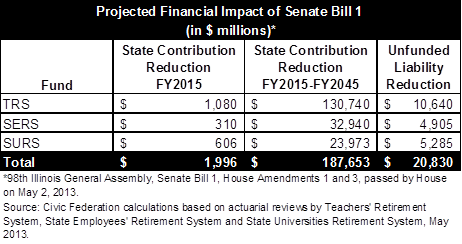

The following table summarizes the results of the actuarial reports on SB1. The reports come from the three largest pension systems—the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS), State Employees’ Retirement System (SERS) and State Universities Retirement System (SURS)—which accounted for 98.5% of the State’s total pension obligations as of June 30, 2012. More detailed information can be found in the reports for TRS, SERS and SURS Actuarial reviews were not available for the General Assembly Retirement System (GARS), and the bill not does not apply to the Judges’ Retirement System (JRS).

According to the actuarial reports, SB1 would reduce the State’s unfunded liability by $20.8 billion. State contributions would decline by approximately $2 billion in FY2015 and by $187.7 billion through FY2045. State contributions under current law are expected to total $7.0 billion in FY2015 and $373.1 billion from FY2015 through FY2045. The State is not expected to recognize savings on pension changes until courts have ruled on legal challenges.

As discussed here, SB1 would cut State costs by reducing the existing compounded automatic annual 3% increase in benefits; delaying the annual increase; phasing in higher retirement ages; capping the salary level on which a pension is based; and increasing employee contributions. The bill would require sufficient State contributions to reach 100% funding by FY2045. The State’s existing funding policy began in FY1996 and requires State contributions to reach a 90% funded ratio by FY2045.

To guarantee that the State makes its required contributions, SB1 permits the pension systems to seek an order from the Illinois Supreme Court compelling the State to make payments. The bill requires the systems to use an actuarial method supported by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board to allocate annual benefit costs. This method, known as entry age normal, smoothes pension costs over time compared with the projected unit credit method now mandated by the State, which increases costs over time.

SB1 also requires the State to make $1 billion a year in supplemental contributions from FY2020 through FY2045 to reduce the unfunded liability. These additional contributions begin as State debt service payments on outstanding pension bonds decline in FY2019. The reduction in pension-related debt payments is attributable to the final repayment of the bonds issued in 2011 to cover State pension contributions.

SB1 is similar to a bill discussed here that was analyzed by actuaries in late 2012. Those actuarial reviews indicated a reduction of approximately $28 billion in the total unfunded liability and savings of about $159 billion on State contributions through FY2045. The projected reduction in unfunded liability from SB1 would be approximately $7 billion less, according to the latest actuarial reports, although State savings on contributions would be substantially higher over time. The smaller projected decline in unfunded liability under SB1 was attributed to the switch to the entry age normal cost method, which reports more costs up front.

The actuarial reviews for SB2404 are more complicated. As discussed here, the bill offers three choices of benefit packages to employees and two choices to retirees. The choices center on reducing or temporarily forgoing the existing compounded automatic annual 3% increase. Potential State savings depend on the choices made by employees and retirees. Retirement systems were instructed to assess the financial impact of various scenarios specified by the General Assembly.

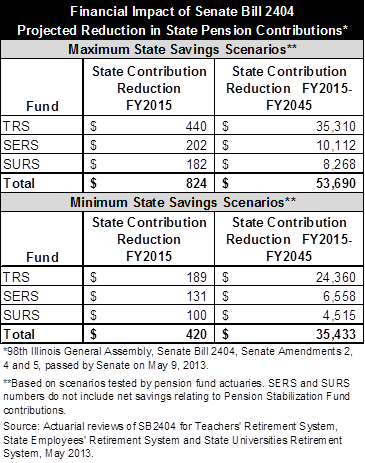

The next table shows minimum and maximum State savings from SB2404, based on the scenarios analyzed by system actuaries. More detailed information can be found in the reports for TRS, SERS and SURS. Actuarial reviews were not available for GARS, and the bill not does not apply to JRS.

It should be noted that SB2404, like SB1, calls for supplemental contributions of $1 billion a year beginning in FY2020. However, the actuarial reports for SERS and SURS did not reflect the impact of those contributions. As a result, total potential savings over time shown in the table above may be somewhat understated. The State’s existing funding schedule, which requires 90% funding by FY2045, would remain in place under the bill.

According to the actuarial reports, the most the State would save on required annual contributions would be $824 million in FY2015 and $53.7 billion through FY2045. Those savings would occur if 1) all employees choose to skip three years of annual increases and to increase contributions by 2 percentage points over two years and 2) all retirees skip two years of annual increases and retain access to health insurance.

On the other hand, the State could save as little as $420 million in FY2015 and $35.4 billion through FY2045. The minimum savings would occur for TRS if 1) all employees choose to switch to a 3% simple annual increase and to skip two years of increases and 2) half of retirees choose to give up access to State health insurance rather than give up existing annual increases. The other systems reported minimum savings under different scenarios.

Senate President Cullerton had said that the bill would lower State pension contributions by $850 million in FY2015 and between $45 billion and $51 billion through FY2045. The Senate President also expected savings of $150 million to $200 million on retiree health insurance in FY2015 and a drop of between $8.5 billion and $15.7 billion in the unfunded liability.

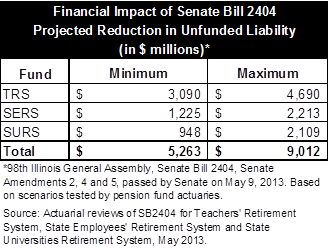

The following table shows minimum and maximum reductions in unfunded liability from SB2404, based on the scenarios analyzed by system actuaries. More detailed information can be found in the reports for TRS, SERS and SURS.

The maximum reduction in unfunded liability shown above is $9.0 billion. This occurs if 1) all employees choose to switch to a 3% simple annual increase and to skip two years of increases and 2) all retirees skip two years of annual increases and retain access to health insurance.

The minimum reduction in unfunded liability is $5.3 billion. This occurs for TRS if 1) all employees choose to skip three years of annual increases and to increase contributions by 2 percentage points over two years and 2) half of retirees choose to give up access to State health insurance rather than give up existing annual increases. The other systems reported minimum savings under different scenarios.

The fate of both bills remains uncertain as the General Assembly winds down its spring session. Meanwhile, three smaller pension bills—dealing with automatic annual benefit increases, retirement age and salary caps—are reportedly under consideration by the Senate. As discussed here, these bills were sponsored by House Speaker Madigan and approved by the House several months ago.