April 04, 2014

As the legal battle over Illinois’ new pension law continues, courts continue to issue rulings on similar pension changes in other states. Last month, Governor Lincoln D. Chafee, General Treasurer Gina M. Raimondo, and the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Board signed off on a settlement agreement to a consolidated lawsuit challenging changes to Rhode Island’s state-administered pension system. If approved by employees, retirees and state legislators, the agreement would make some changes to the groundbreaking pension reform package passed by the General Assembly in November 2011. The parties to the lawsuit had been in court-ordered mediation for over a year.

In follow-up to two previous posts on the Rhode Island pension reforms, this blog will outline the changes to the reform package made in the proposed settlement, how they change the projected savings of the reforms and the next steps in the reform process. The two previous posts explain the reform package and provide an update as of February 2014.

The original Rhode Island Retirement Security Act of 2011 (RIRSA) included a suspension and reduction of cost-of-living adjustments, an increase to the retirement age and a new hybrid pension benefit plan, among other changes. The law went into effect July 1, 2012 and in December 2012, Judge Sarah Taft-Carter ordered both sides of a series of lawsuits challenging the law into mediation.

The Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI) is a defined benefit pension plan for state employees and teachers. ERSRI additionally administers and invests the assets of the Municipal Employees’ Retirement System (MERS), the State Police Retirement Benefits Trust and the Judicial Retirement Benefits Trust. All assets are comingled for investment purposes, though their actuarial valuations are determined separately.[1]

The following analysis will focus on changes to benefits provided through ERSRI to the two largest funds, State Employees and Teachers, though additional adjustments are proposed for various benefits provided through MERS.

Provisions of the Proposed Settlement Agreement

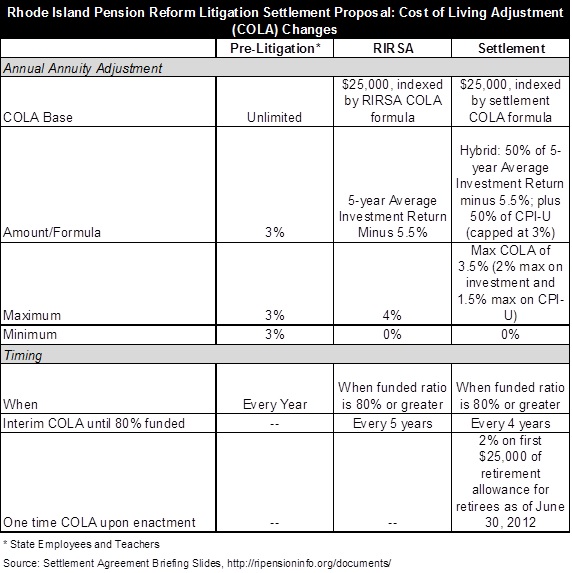

The proposed settlement announced on February 14, 2014 would not only end the litigation associated with RIRSA, but also settle lawsuits contesting changes made to pensions in 2009 and 2010. The main change to the RIRSA reforms for all participants is to the cost of living increase. There are additional major changes to benefit accrual for employees with 20 or more years of service.

The following table summarizes the pre-RIRSA annual automatic annuity increase, changes made to annual adjustments under RIRSA and the changes proposed under the settlement. The COLA changes apply to all plans covered by the RIRSA reforms.

In addition to the changes to automatic annual increases to Teachers’ and State Employees’ annuities, the settlement agreement would make significant changes to the retirement benefits for employees who had 20 or more years of service as of the effective date of RIRSA, June 30, 2012.[2]

One of the innovative aspects of the 2011 Rhode Island pension reform package was the fact that it moved current employees from a defined benefit (DB) plan to a hybrid plan with a slower-accruing defined benefit plan and a supplemental defined contribution (DC) plan. Previously earned benefits for vested employees were frozen and future benefits were to be accrued at a lower rate. Proponents of the reform asserted that the hybrid structure would provide a similar level of benefits to workers as a DB plan, but with shared risk between the employee and taxpayer.

Under the settlement agreement, teachers and state employees with 20 or more years of service as of June 30, 2012 remain under RIRSA until June 30, 2014 and thereafter will no longer participate in the defined contribution plan. Instead, they will keep the DC assets they accrued in the two years they participated but only participate in a DB plan going forward. The accrual rate for the DB plan will be 2% of final average salary per year. The accrual rate for the DB portion of the hybrid plan under RIRSA was 1% and before RIRSA ranged from 2.0% to 3%, depending on years of service and when the employee became a member of the fund. To somewhat offset the cost of this change, employees will be required to contribute a higher percentage of their salary. Prior to RIRSA, teachers contributed 9.25% of salary and state employees contributed 8.75%. Under the settlement agreement, members of both groups with 20+ years of service will be required to contribute 11% of salary.

For teachers and state employees who had fewer than 20 years of service as of June 30, 2012, the hybrid DB/DC plan will remain in place and the DB portion will continue to accrue at 1% of final average salary per year. However, the employer contribution to the employee’s individual account under the DC portion of the benefit will increase for those employees with 10-20 years of service from 1% of salary to either 1.25% or 1.5%.[3] Employee contribution rates do not change for employees with fewer than 20 years of service.

Costs of the Settlement Agreement

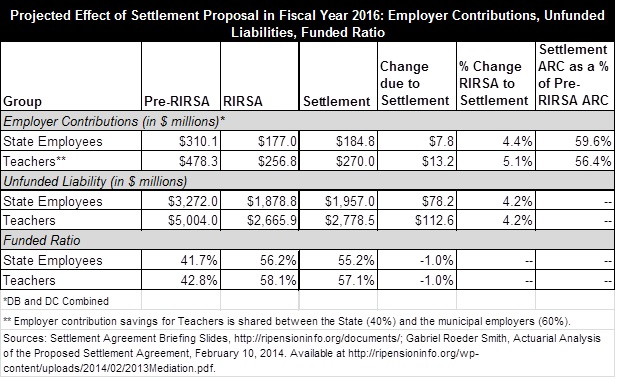

The effect of RIRSA’s changes to benefits was to immediately lower the unfunded liabilities of the pension plans, increase their funded ratios and decrease required employer contributions. Because pension benefit levels would be higher under the provisions of the settlement agreement, actuaries have projected that the proposed changes in the agreement will, for the Teachers and State Employees funds, slightly increase unfunded liabilities, slightly decrease funded ratio and modestly increase required State and local government employer contributions.

The following chart summarizes the costs of the settlement agreement to the State Employees and Teachers plans in comparison to the original pension reform package.

The total state share of employer contributions for all pension plans covered by the reforms will increase by $13.1 million or 4.7%. The total municipal share of employer contributions will increase by $11.1 million or 5.4%. Ninety-five percent of the savings from the original pension reform will be preserved with the settlement, according to proponents.

Next Steps

The plaintiffs to the consolidated lawsuits and the state legislature will need to agree to the settlement for it to move forward and become law. First, all of the members of the retirement system will need to vote on the settlement. If more than 50% of any one group of retirees and employees votes against the settlement proposal, the litigation will continue.

If the plaintiffs sign off on the agreement, Judge Sarah Taft-Carter will conduct fairness hearings and determine whether or not to approve the settlement agreement and turn it into a class-action lawsuit. If the court conditionally approves the settlement, the plaintiffs will vote again. If the court signs off, the General Assembly can 1) enact the settlement; 2) take no action and the litigation will continue; or 3) amend the settlement and the original litigation will continue.

According to the union plaintiffs coalition, the ballots on the settlement agreement were sent out mid-March. In order to follow the terms of the settlement agreement, the voting must be completed within 60 days of February 14, 2014. Ballots not returned will be counted as “yes” votes.

Union leaders have generally joined Governor Chaffee and Treasurer Raimondo in supporting the settlement, though some rank-and-file members have noted their opposition to the plan. Municipal leaders’ reaction has been mixed, with some saying their taxpayers cannot afford the increases to contributions projected under the settlement.

[1] The Municipal Employees Retirement System (MERS) is locally funded, not state-funded. However, not all communities in Rhode Island are enrolled in MERS.

[2] Other changes not examined in this blog include revisions to retirement age and early retirement.

[3] Employer contribution rates are higher for employees without Social Security.