April 20, 2018

The Civic Federation has long supported the development of a consensus revenue forecast for the State of Illinois. Public finance experts recommend that the executive and legislative branches reach agreement on a revenue forecast prior to the publication of the Governor’s annual budget to help ensure the review of critical assumptions, remove the forecast from ongoing dispute and keep the budget process on track.

It is technically too late to implement that process for the 2019 budget year, which begins on July 1, 2018. Governor Bruce Rauner presented his recommended FY2019 budget on February 14, and the General Assembly’s fiscal analysis unit issued its initial revenue forecast for FY2019 about two weeks later.

However, legislative leaders have agreed to the Governor’s request to establish their own official revenue estimate to be used as the basis for negotiations with the Governor’s staff on the FY2019 budget. For several years beginning in 2011, the budget approved by the legislature used revenue estimates originating in the House. The stated purpose was to set spending caps based on the House revenue forecasts. The process stopped during the State’s budget impasse in FY2016 and FY2017, when the Governor and General Assembly were unable to find a way to deal with the revenue shortfall caused by the rollback of temporary income tax increases.

As discussed here, the Governor’s proposed FY2019 budget relies on higher income tax rates enacted in 2018 over the Governor’s veto. Effective on July 1, 2017, individual income tax rates were raised to 4.95% from 3.75% and corporate income tax rates to 7.0% from 5.25%, generating an estimated $4.5 billion in additional revenue in FY2018.

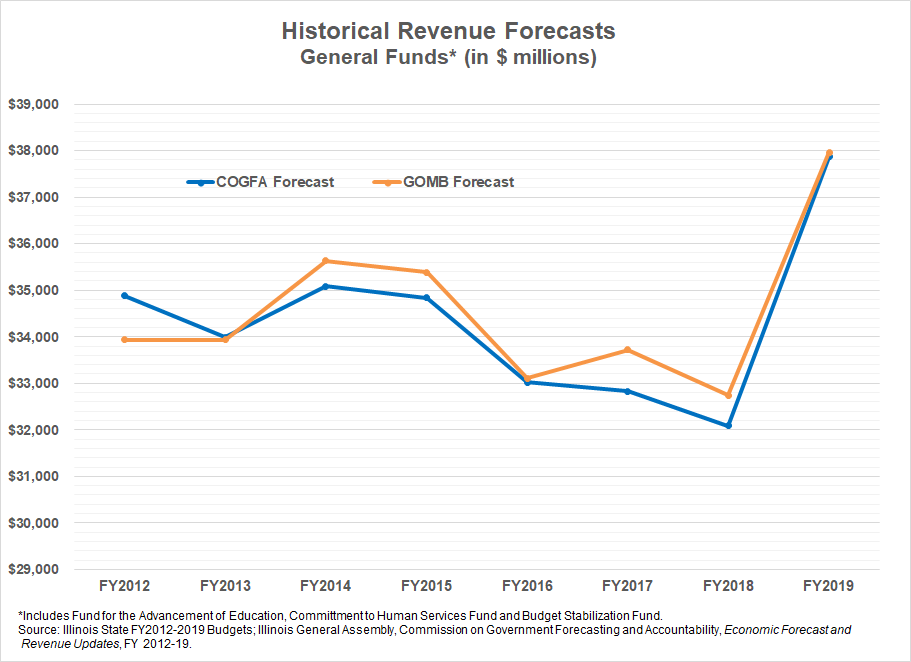

Going into FY2019, revenue forecasts by the executive and legislative branches are $99 million apart—less than 0.3% of expected revenues and among the closest they have been in recent years. The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB) forecasts General Funds revenue of $37.96 billion in FY2019, while the legislature’s Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (COGFA) forecasts $37.87 billion. Both of these numbers include one-time revenues of $300 million from the proposed sale of the James R. Thompson Center in Chicago and $600 million in borrowing from other State funds, which the Governor does not plan to repay.

The following chart compares the General Funds revenue forecasts of COGFA and GOMB for FY2012 through FY2019. Although both agencies provide updated forecasts, the numbers in the chart are initial forecasts, issued several months before the beginning of the given fiscal year. COGFA and GOMB rely on some of the same outside consulting firms for economic forecasting.

The forecasts largely track each other, with differences of less than $100 million in FY2013, FY2016 and FY2019. However, in some years there were significant discrepancies. The largest difference was in FY2012, the first full year of the temporary tax increase, when it was more difficult to forecast how taxpayers would react to the higher rates. COGFA’s projection for individual income tax revenues exceeded GOMB’s by $831 million.

FY2014 was the only year in which COGFA and GOMB used different assumptions for the percentage of personal and corporate income tax collections that would be diverted to the Income Tax Refund Fund in order to support refunds for tax filings. That year COGFA assumed 9.75% for personal income tax and 14% for corporate, while GOMB assumed 9.0% and 12%, respectively. Nevertheless, the net difference in the forecasts of the two agencies for income tax was only $68 million.

Federal revenue estimates were a major source of the discrepancy in FY2017. Federal revenues, consisting mainly of reimbursements for State Medicaid spending, represent a large component of General Funds revenues. In 2017 COGFA lowered its estimate of federal revenues by about $450 million, reflecting the federal government’s recent practice of deducting amounts owed for Medicare premiums from other reimbursements instead of waiting to be paid by Illinois. GOMB returned to a similar methodology a year later.

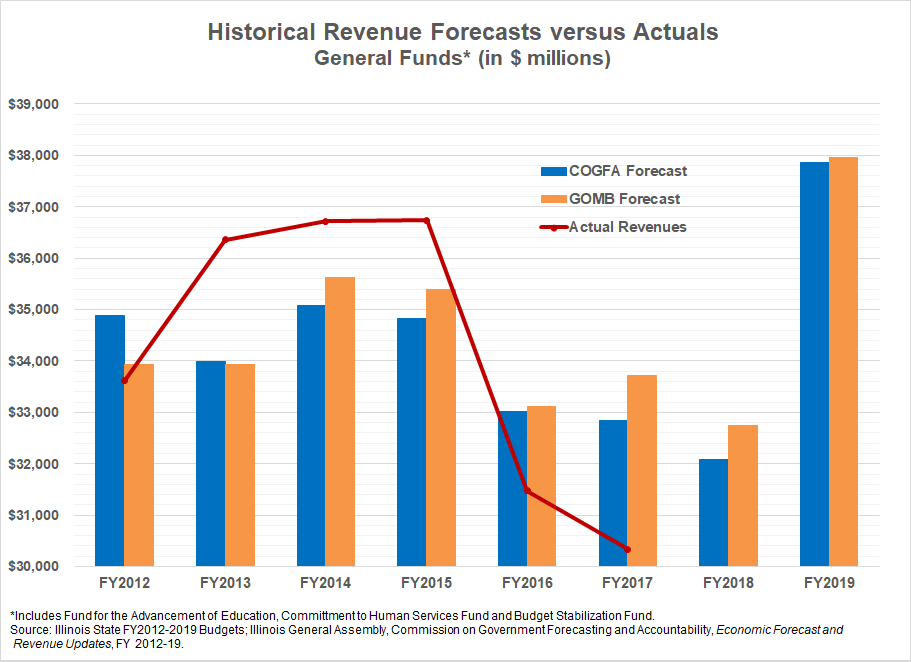

Coming to a consensus revenue forecast is much easier than accurately forecasting future revenues. The most frequent reason that actual revenue varies from projections is when the State changes policy. For instance, to help replace the expiring temporary tax increases in FY2015, the State used resources that were not included in either forecast: $1.2 billion in transfers from other funds and $377 million of interfund borrowing. Similarly, both forecasts for FY2018 assumed the continuation of then-current income tax rates, but the General Assembly raised the rates as part of its budget package. The legislature also began excluding tax receipts distributed to local governments and transit districts from General Funds revenues and expenditures.

Revenue estimates can also be thrown off by external factors. In April 2013 the State received an extra $1.0 billion of income taxes due to taxpayer strategies to avoid higher federal tax rates. A surge of this type is often referred to as an “April Surprise.”

Another major driver of inaccuracy in forecasting is the difficulty of predicting the timing of federal Medicaid reimbursements, which depend on patterns of State spending. Due to budgetary problems, the State may delay paying budgeted Medicaid bills for a given fiscal year by as much as six months. Because federal reimbursements depend on State Medicaid spending, revenue related to on those bills will not be reflected in the budget until the next fiscal year. During FY2016 and FY2017 when the State lacked a comprehensive budget, cash flow strains delayed the payment of Medicaid bills, resulting in lower than forecast Federal reimbursements.

The following chart shows the actual revenues compared with the forecasts prepared by both COGFA and GOMB.

A study on tax volatility by the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government found that state estimates of combined income and sales tax revenues were off by 3.3% from 1987 to 2013. Illinois at 3.9% was near to the national average.

However, the study also noted that both revenue volatility and forecasting errors have been growing in magnitude nationwide. While the economy itself became more volatile, revenue fluctuations exceeded those of the economy, in part due to increasing reliance on capital gains and other non-wage income.

The study also noted that while consensus revenue forecasts have not significantly helped states to reduce forecasting errors, they are valuable for other reasons. A follow-up analysis by Pew concluded that the best strategy for States to manage revenue volatility is to build adequate reserves.

Illinois has the opposite of reserves—the State’s unpaid bill backlog stood at nearly $8.6 billion as of April 20, 2018. Adopting a consensus revenue process is only one small step toward restoring the State’s fiscal balance.