October 09, 2025

by Grant McClintock

See the Civic Federation's October 16 statement in response to the City of Chicago FY2026 Proposed Budget here.

Chicago enters the FY2026 budget season at a pivotal moment. If it feels like we have been here before, it is because we have for as long as can be remembered. Ever-mounting taxes and fees, persistent structural budget gaps, high long-term debt, underfunded pensions, and debates over government spending are long-held staples of local political discourse. Despite occasional wins, the City’s fiscal situation remains largely unchanged, and new financial burdens further threaten an already fragile situation.

The City’s net operating budget (not including grant funds) increased by 39.8% from FY2019 to FY2025, subsidized in large part by temporary federal pandemic funding that kept the City financially afloat and funded critical services. The pandemic is over, but many of the programs and personnel positions established during that time remain, and without the benefit of the federal funding that previously supported them. To balance the budget against this backdrop, the City must implement substantial operational savings and cuts, as well as likely revenue increases on an already heavily burdened tax base.

The City faced precisely the same challenge at this time last year during the FY2025 budget process. Unfortunately, it failed to meet that challenge, passing a budget backed by several small revenue increases that provided only limited, short-term structural relief. With an even larger deficit looming for FY2026 than last year and fewer options to address it, the upcoming budget process will test whether the City can move beyond a history of temporary solutions at the margin and toward longer-term fiscal stability.

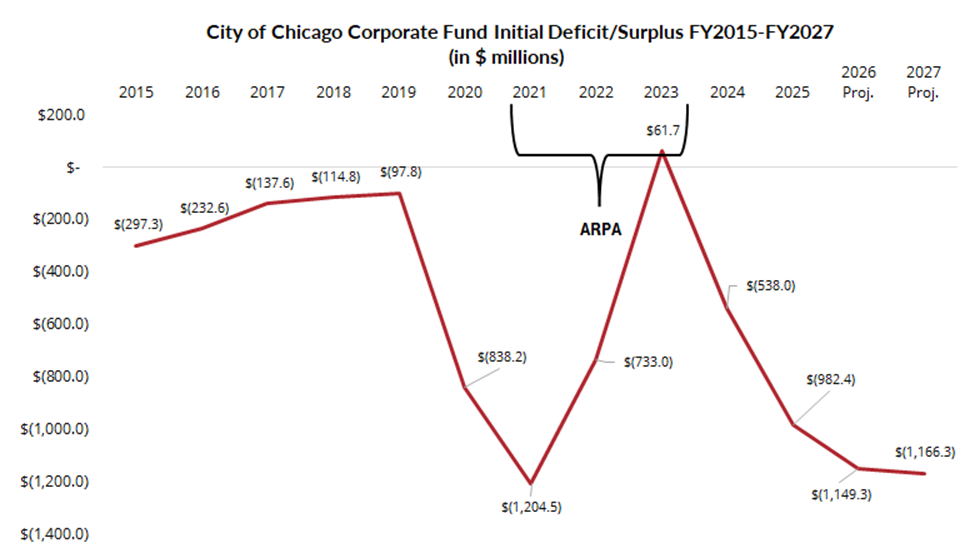

The FY2026 projected deficit is the largest the City has ever faced, with the exception of FY2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic when the City faced a comparably sized deficit. Equally concerning is that the historical availability of financial backstopping from the State and Federal governments, which were long the norms, is now abruptly and severely constricted. It has been suggested in recent days that the City only faces a “revenue challenge.” The reality is more complex. The so-called revenue challenge is at its core the product of a long-term spending problem. Put simply, Chicago has habitually spent money the City didn’t have. As a result, the City’s budget challenges must be understood as a function of both recent and long-term fiscal decisions that have left little margin for flexibility today. The revenue challenges can, and must, be minimized through emphasis and prioritization of operational savings and cuts.

The reality for FY2026 is unprecedented and fundamentally different from any year in the City’s modern history. With no easy answers or untapped reserves to draw from, this moment calls for difficult conversations and a focus on long-term solutions.

The following sections outline the key fiscal issues shaping this year’s budget and highlight what has changed since the FY2025 budget cycle. The Civic Federation will closely monitor these and other issues as the Mayor introduces the proposed FY2026 budget and City Council hearings commence.

I. Structural Budget Deficit

What’s Changed

- Federal pandemic stimulus funds (ARPA) are gone, removing a major source of budget relief.

What to Look Out For

- Whether the Mayor’s FY2026 budget proposal relies on new recurring revenues and suggests sustainable savings and cuts, or instead leans on temporary or one-time fixes that will perpetuate and possibly exacerbate existing long-term structural imbalances.

For more than 20 years, Chicago has operated under a structural budget deficit, meaning revenues have consistently been insufficient to keep pace with increasing expenditures, resulting in budget gaps.

At this time last year, the City projected a $1.12 billion budget deficit for FY2026. The most recent Budget Forecast released in August slightly revised that number to $1.15 billion. This staggering number, which is only expected to increase in FY2027, is nearly as high as the deficits faced during the height of the pandemic. The difference today, however, is that during the pandemic, the City had the benefit of federal stimulus funding through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to maintain a balanced budget for three years. Now, those funds have been almost fully spent, with all remaining funds earmarked for recovery programs. The chart below illustrates the trend in budget gaps since 2015.

The budget proposal introduced by the Mayor will need to solve for a $1.15 billion budget gap, and it remains to be seen what mechanisms will be used to close this year’s deficit. In the past, and against best financial practice, the City has relied on one-time revenues to fill budget gaps, such as debt refinancing, asset sales (parking meters, etc.), sweeps of tax increment financing (TIF) funds, and spending down operating reserves. A deficit of this magnitude will call for more substantive, long-term solutions to improve the City’s financial position, ideally through a combination of both efficiencies and revenues.

II. Uncertainty of Federal Funding

What’s Changed

- The federal government has signaled potential cuts or holds on infrastructure, health, and community development funding.

What to Look Out For

- Whether and how the Mayor’s FY2026 proposed budget plans for possible declines or delays in federal funding.

The federal government’s threats to withdraw existing grant funding to states and localities in areas such as infrastructure, environment, public health, and community services are creating a level of uncertainty for the City of Chicago and its sister agencies. For example, the White House recently announced it was withholding $2.1 billion in federal funds for the Chicago Transit Authority to extend the Red Line south. While the City itself has so far been able to head off any significant losses in federal funds, this has required diverting time and resources into litigation. A more probable outcome is that the receipt of grant funds could be significantly delayed. The magnitude of federal funding that supports Chicago’s budget is not slight, representing over $1 billion annually, although the amount fluctuates based on the timing of when grant funds are received and spent down. Some of the City’s largest areas of grant funding that have been the focus of threats from the federal administration include the Department of Public Health, the Chicago Department of Transportation, and public-safety-related departments (police, fire, emergency management)—each representing hundreds of millions in grant funds.

At the State level, Governor Pritzker recently issued an executive order directing Illinois agencies to identify up to 4% in reserves to mitigate possible negative impacts to services. With the federal government showing that it is no longer a stable partner to states and local governments, the City would be well-served to consider how it will sustain programs in the event that some federal funds are cut or delayed.

III. Credit Downgrades

What’s Changed

- Three credit rating agencies downgraded the City’s rating or outlook in the past year, citing a persistent structural deficit, use of one-time revenues, a reluctance to cut spending, and, for Fitch, the passage of an infrastructure bond with a backloaded payment structure.

What to Look Out For

- Whether actions taken in the FY2026 budget include sustainable structural reforms sufficient to elicit a favorable assessment from the credit rating agencies.

The City’s inability to rein in its structural deficit has led to three credit downgrades in the past year. Following the passage of the FY2025 budget, in January 2025, S&P downgraded the City’s rating from BBB+ to BBB, citing a persistent structural deficit, use of one-time revenues, and a reluctance to cut spending. The same month, Kroll downgraded the City’s long-term general obligation (GO) bond ratings from A to A- for similar reasons. In May 2025, Fitch revised the City’s outlook from stable to negative following the passage of an infrastructure bond with a backloaded payment structure (explained further below). While these downgrades do not immediately impact the FY2026 budget gap, they will increase the City’s borrowing costs in the future.

IV. Property Tax Pressures

What’s Changed

- The 2024 Chicago reassessment increased the residential share of Chicago’s taxable property value to 54% from 49% after assessments and appeals were finalized by the Cook County Assessor and Board of Review, largely due to declines in commercial values.

- The County’s ongoing property bill delays mean that Chicago and all other Cook County governments have not yet received the second tranche of property tax revenues that normally would have been collected in August.

- Political resistance to property tax increases remains strong, even as fiscal pressures mount.

What to Look Out For

- If the FY2026 budget includes a property tax increase, whether it is minimized through maximization of sustainable structural savings in operations.

The property tax situation in Cook County is creating pressure on all sides, with taxpayers feeling overburdened and declining commercial real estate values shifting more of the burden to homeowners. Chicago’s recent tri-annual property tax reassessment, completed in 2024 and applicable to tax bills paid in 2025, is likely to place further strain on the same taxpayers. This has already been happening, as a report published by the Cook County Assessor in May found that the Board of Review appeals process resulted in cuts to commercial property values, thereby increasing the residential share of the property tax burden from 49% to 54%.

Further complicating Chicago’s property tax challenges is a substantial delay in billing. As of the publishing of this report, property owners in Cook County have yet to receive their second installment bills for tax year 2024, normally distributed in the summer, due to complications from a years-long technology upgrade. Delayed bills result in delayed collections, which impact the government’s ability to make required payments and fund critical services. This recently manifested in the City using $28 million from its cash reserves to make a payment to the fire pension fund. The delay in second installment property tax bills could further impact first installment bills next year, adding to the cycle of delayed tax collections. Although these revenues will eventually be collected, the delays create cash instability for Chicago and its sister agencies.

Although a property tax increase is politically unpopular, it is one of the few revenue sources fully under the City’s control that could generate enough revenue to make a dent in the City’s budget deficit. The Mayor has all but ruled out any increases to property taxes, but this goal may conflict with reality when faced with such a large deficit. A property tax increase should not be ruled out, but rather implemented only after all available efficiencies are enacted. The City faces the difficult task of striking an appropriate balance between raising sufficient revenue while not overburdening taxpayers.

V. Budget Process Improvements

What’s Changed

- The Management Ordinance requires a Mid-Year Budget Report from both the Office of Budget and Management and the Council Office of Financial Analysis (COFA), as well as a series of mid-year public hearings.

- The Mayor convened a working group to assess potential revenues and efficiencies, with an eye to both the 2026 budget year and long-term planning.

What to Look Out For

- Whether these new oversight mechanisms are effectively informing policymaking, and whether they translate into actionable reforms in the FY2026 budget proposal.

The City and Mayor Johnson have made some improvements in terms of budget process transparency and long-term planning. Last year’s Management Ordinance (although significantly watered down from its original version) enacted increased budget monitoring requirements. The ordinance includes a Mid-Year Budget Report from the Office of Budget and Management that contains analyses of revenues, expenditures, workforce, and grant funding. The ordinance also requires a series of public hearings for Council members to question various departments on the data. It further requires a Mid-Year Report from the Council Office of Financial Analysis (COFA) outlining options for revenues, cost savings, and efficiencies, as well as a trend analysis in municipal financing and an analysis of vacancy carryover and overtime. These reports are intended to help City Council conduct a more thorough analysis of the proposed budget. With 2025 being the first year these requirements were implemented, the City Council should continue to refine the information disclosed and ensure the information is being used to the Council’s benefit.

This year has also seen more engagement with long-term financial options. In April, the Mayor convened the Chicago Fiscal Sustainability Working Group, comprised of business, civic, labor, and community leaders, to assess the ways the City could address its mounting deficits through revenues and efficiencies. Their work was supplemented by work from Ernst & Young, which secured a $3.2 million contract with the City to examine its finances and identify structural solutions. The Working Group released its Interim Report in September, laying out 89 revenue and expenditure options and confirming that there are no easy answers to resolve the City’s structural budget deficit. As the Federation noted in a recent assessment of the report, though many of the options presented are not feasible for FY2026, the report is a starting point for the long-term efforts that will need to take place. In short, although there is still significant work to be done to improve transparency, oversight, and long-term planning within the budget process, this year has shown heartening improvements.

VI. Tensions with Chicago Public Schools

What’s Changed

- CPS’ decision to stop reimbursing the City for the Municipal Employees Annuity and Benefit Fund (MEABF) payment has put the burden back on the City to cover the full cost, adding to Chicago’s year-end deficit.

- CPS’ FY2026 budget assumes $379 million in TIF surplus, a figure that is dependent on City decisions this budget cycle.

- The Board of Education is now partially elected, complicating intergovernmental coordination.

What to Look Out For

- Whether the Mayor’s FY2026 budget proposal, or accompanying legislation, includes steps to resolve the MEABF reimbursement issue or clarify shared financial responsibilities between the City and CPS.

Coming off a hotly debated Chicago Public Schools (CPS or the ‘District’) budget season this summer, the financial entanglements between the City and CPS are no closer to resolution. The Federation has been on record for years on the need for the two governments to resolve these issues, particularly as the District transitions to a fully elected Board of Education (the ‘Board’) in 2027, which further complicates the power dynamics with City Hall.

The biggest sticking point is whether CPS will reimburse the City for the annual pension payment to the Municipal Employees Annuity and Benefit Fund (MEABF) for non-teacher CPS employees. The City traditionally covered this cost, but CPS began reimbursing the City in FY2021 with surplus funds thanks to federal pandemic relief. After federal funding lapsed, the City asked the District to continue making the payments. But CPS, facing its own budget constraints, found it in its best interest to push these payments back to the City. Contention over this payment ultimately led to the mayoral-appointed CEO and several appointed board members rebuking the Mayor by refusing to make the payment and take out a short-term loan to cover the costs. Ultimately, the Board passed a FY2026 budget that dismissed the Mayor’s demand for short-term borrowing to cover the payment, which contributed to the City ending FY2025 with a $146 million deficit. Overall, the CPS FY2025 budget cycle made one thing very clear: absent changes at the State level or additional funding sources, CPS will not be reimbursing the City for the MEABF payment in the near future, and it will need to budget accordingly.

Another CPS budget conflict revolved around the projected size of the City’s TIF surplus. The FY2026 CPS Budget assumed $300 in TIF surplus and received an additional $79 million over the summer after the City took even more surplus funds. The District is basing its FY2027 projections on the same level, which would require the City to surplus approximately $700 million. Therefore, whether or not the City sweeps enough TIF funding to support CPS’ budget will be an urgent question in the City’s budget process. This is further complicated by the City’s own reliance on TIF as a revenue source to fill its own budget gap. The fiscal relationship between the City of Chicago and CPS remains a major source of budget uncertainty this year and into the future.

VII. Cost Drivers

What’s Changed

- Passage of HB3657 expanded pension benefits for police and fire funds, adding $11.5 billion in long-term liabilities and $7 billion in additional payments through 2055.

- The City issued an $830 million bond with a back-loaded payment structure, increasing total costs to $2 billion.

- As in past years, the City has gone vastly over budget on overtime. Within CPD in particular, overtime spending has reached $190 million so far in 2025 compared to $100 million budgeted.

- FY2025 judgment and settlement payouts have already exceeded the budget by more than $120 million.

What to Look Out For

- Whether the proposed FY2026 budget includes programmatic measures to contain and reduce overtime spending and reliably manage vacancies in relation to operational needs, most particularly with respect to police department staffing.

- Whether the Mayor’s FY2026 budget proposal realistically accounts for judgments, settlements based on historical trends, and analysis of existing liability exposure.

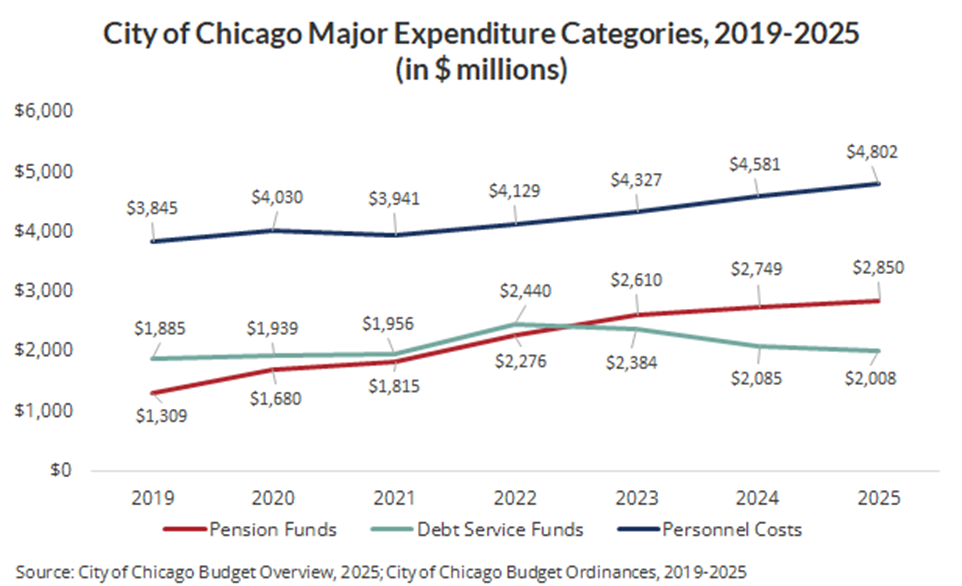

There are a number of underlying factors and issues that continue to drive the City’s ballooning expenditures and constrain its flexibility to close future deficits. Chief among these are pension and debt obligations, personnel-related costs, overtime, and ongoing judgments and settlements. Each reflects long-standing structural issues that, taken together, threaten to crowd out essential public services and investments.

Pensions and Debt: In FY2025, pension and debt service payments together accounted for approximately 40% of the City’s operating budget. Pension fund contributions alone accounted for 23.5% of the City’s operating budget in FY2025. Despite such large payments being funneled towards these liabilities each year, the City’s pension funds remain among the most poorly funded in the nation.

Against the urging of local civic officials, Governor Pritzker recently signed a law enhancing Chicago’s police and fire pension funds as a means of addressing Tier 2 pensions. The measure, HB3657, has the potential of driving the two funds into insolvency, yet it was unanimously passed through both State legislative chambers at the end of the spring legislative session in a matter of days with minimal pushback from the City. The bill attempts to bring the funds into compliance with Social Security Safe Harbor regulations that require public pension benefits to be comparable to retirement benefits a worker would receive under Social Security. However, the legislation doesn’t resolve the Safe Harbor compliance issue on a permanent basis. The bill adds $11.5 billion to the City’s long-term liabilities and a total of $7 billion in additional pension contributions through 2055. The legislation did not address the City’s other two funds—Municipal and Labor. Both of these funds will still need state action to address Safe Harbor compliance for Tier 2 pensioners, which will inevitably add even more to the City’s future pension costs. The Mayor’s pension working group, formed in 2023, quietly disbanded without providing any public information or recommendations about how to resolve this issue.

Adding to its future long-term debt, in February, the City approved an $830 million General Obligation Bond to fund infrastructure improvements across the City. While borrowing for infrastructure is a common practice, the specific terms of the deal raised alarm bells. Namely, the backloaded nature of its payment structure will increase the overall price of the bond to $2 billion, with no principal payments until 2045. These terms fall far short of ideal and place the burden on future generations to fund current projects.

Personnel and Overtime: The City’s overtime costs continue to be a financial challenge, particularly within the Chicago Police Department (CPD). Chicago spent a total of $510.9 million on overtime in 2024. Of this amount, $273.8 million was within CPD—nearly three times the $100 million budgeted for the year. Using slightly different time metrics, a dashboard launched by the Inspector General in July shows that the City has paid $244.4 million in total overtime earnings over the last 12 months. So far in 2025, based on the same dashboard, CPD has spent $190 million on overtime compared to $100 million budgeted. Much of the issue surrounds staffing levels: the FY2025 budget included 1,155 vacant officer positions and hundreds more across civilian and exempt positions. If these vacancies remain unfilled, the Department must determine how to operate more efficiently with its existing workforce.

The City is currently undertaking a long-promised workforce allocation study of CPD aimed at addressing some of these issues. It is imperative that this study identify solutions to the underlying management problems, establish a methodology for data-driven deployment with geographic accountability and scalability based on staffing changes, and support better oversight structures. Whether the workforce allocation study will be made publicly available in the coming fiscal year remains to be seen. The Federation continues to stress the importance of this study and the need to empower an office of risk management to play a key role in increasing departmental efficiencies.

Judgments and Settlements: Chicago repeatedly exceeds its budget for judgments and settlements, which places strain on other areas of the budget. The FY2025 budget allocated $82 million towards judgments and settlements against the City and had already exceeded that amount midway through the fiscal year, with an additional $35.2 million settlement in July, a $90 million payout in September, and 275 cases in the pipeline. Because the City routinely exceeds its budgeted amounts, the remaining costs are often funded through borrowing or through the ambiguous ‘Finance General” budget category. Given the City’s financial condition, a more realistic line-item amount should be budgeted.

Conclusion

The FY2026 Chicago budget cycle will test the City’s ability to transition from the status quo or temporary solutions toward long-term, sustainable fiscal practices. As Mayor Johnson’s FY2026 budget proposal is presented, debated, and amended, the Civic Federation will focus on whether it:

- Reduces reliance on one-time revenues and borrowing;

- Implements recurring, equitable revenue sources;

- Demonstrates transparency and data-driven oversight;

- Advances structural reforms to pensions, workforce management, and intergovernmental coordination.

Chicago’s fiscal challenges are long-standing, but they are not insurmountable. Addressing them will require difficult decisions and a renewed commitment to transparency, accountability, and long-term planning.

For the what to look out for, I don’t what this means in this context. It is not where this issue is will be resolved. All that could be resolved is for the FY2026 to be based on reliable assumptions respecting this obligation that is legally the City’s under current law.