October 08, 2025

by Grant McClintock

Chicago is the only major city in the United States that operates without a constitution, which, for cities, is referred to as a charter. This absence is not just an anomaly; it fundamentally impacts every aspect of our City’s processes. Without a charter, Chicago’s governance rests on a patchwork of ordinances and informal traditions that can change with each administration. This has created a system with no clear separation of powers, limited resources for the City Council to serve as a co-equal branch, and little transparency in operations or documentation.

The result has been chronic deficiencies in accountability, transparency, and fiscal discipline, all of which manifest in poor outcomes for the City. Certain infamous decisions, such as the “parking meter deal”, could only have occurred because the City Council lacked a comprehensive process for vetting large contracts. Other large-scale City deficiencies, such as its documented culture of corruption, stem from a lack of oversight over elected officials and opaque City processes.

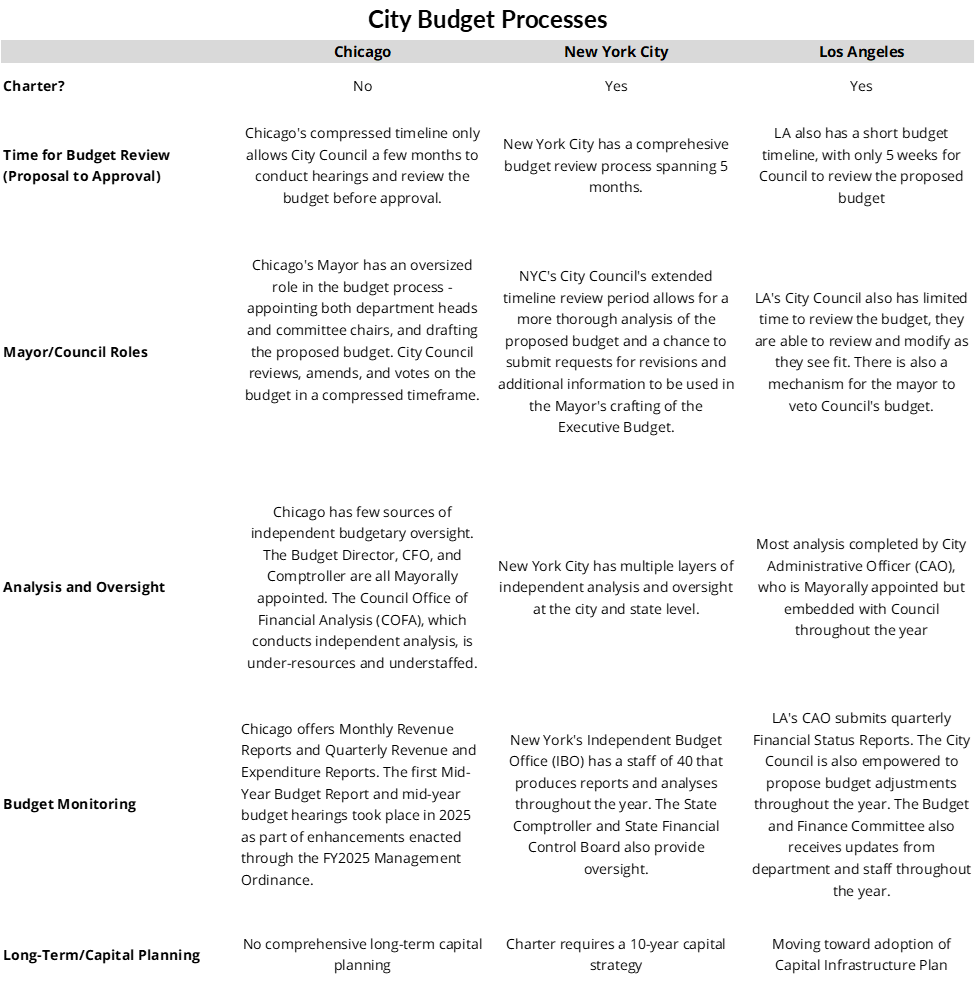

Ultimately, it is the absence of an enforceable structure that allows for these problems. By contrast, other major cities like Los Angeles and New York City are governed by a charter and have clearer separation of powers, greater transparency, and stronger accountability (see a comparison chart for a full breakdown.) Their structures are not perfect, but having a charter provides some of the safeguards Chicago lacks. Given the increasing instability of federal support for state and local governments, a charter is not simply an option, but a necessity that would provide lasting checks and balances and implement guardrails to improve Chicago’s financial outcomes and decision-making.

How would a City Charter Improve the Chicago Budget Process?

When examining specifically how the City crafts its annual budget, Chicago’s power dynamics have resulted in a weak City Council that has historically served as a rubber stamp for the Mayor’s proposed budget. A municipal charter could improve Chicago's budget process by rebalancing power between the Mayor and City Council and providing more effective financial oversight. This would facilitate a more transparent, accountable, and stable budgeting process.

As part of the Civic Federation’s series on city charters and how one could help Chicago, this piece focuses on how charters can provide a framework for municipal budget processes. Using examples from Chicago’s two largest peer cities, New York City and Los Angeles, we find that city charters can provide important guardrails, resulting in a more equal distribution of power between branches of government and more extensive, independent analysis of financial information. A city charter can establish parameters for when the budget is introduced and adopted, as well as the roles of each government branch in crafting, amending, and approving the budget. Additionally, it could facilitate transparent short- and long-term monitoring of revenues and expenditures throughout the year.

While Chicago’s budget process includes many of the same key elements as other cities, it lacks the cohesion and legal framework that make those processes effective. Built from a hodgepodge of norms, State requirements, and City ordinances, Chicago’s system lacks a unifying vision or accountability mechanism.

The result of this lack of coordination is a system that significantly empowers the Mayor of Chicago – far more than in peer cities – at the expense of the independence of the City Council. The Mayor’s Office controls the initiative in the budget process by deciding when to release a proposed budget, controlling budget and finance information, under-resourcing the Council, and keeping mid-year budget adjustments largely within the executive branch. The City Council, with little time, information, or capacity to independently analyze the budget, is generally known to rubber-stamp the Mayor’s proposed budget, and the public is left with little transparency as to how budgeting decisions are made.

In contrast, both the Los Angeles (LA) and New York City (NYC) charters establish rules for submissions, deadlines, required reports, and council-mayor interactions. NYC’s expansive charter outlines a comprehensive budget process, with quarterly budget updates, multiple sources of independent oversight, and a much longer budget approval process than Chicago. Los Angeles’ charter also enshrines the separation of powers by codifying specific powers for both the Mayor and the City Council and by laying out a veto process which gives both the Mayor and the Council the power to veto each other’s amendments to the budget under certain circumstances.

When adopting a municipal charter, Chicago could learn from its peer cities and establish a structure and process for creating the annual budget. This would empower Chicago’s City Council to have a real voice in the budget process, and by extension, empower voters, whose primary ability to impact City policy is choosing their alderperson. A clear budget process would also provide transparency, forcing the Mayor’s Office to justify the decisions made in its proposed budget to the Council and requiring regular, comprehensive reports on the state of the budget. Ultimately, a charter could remove Chicago’s reliance on mayoral discretion and informal practices, making the City’s budget process more accessible and understandable to government officials, business leaders, voters, and all other stakeholders within the City.

1. Better Define the Roles, Responsibilities, and Powers of the Mayor and City Council

The City Council plays a weak role in the Chicago budget process due to its cumbersome size, committee structure, and lack of capacity to conduct independent analysis. These structural disadvantages make it difficult for the Council to act as an equal branch of government to the Mayor in the budget process.

Under Chicago’s strong mayoral system, the Mayor (the executive branch) has exclusive authority to propose the annual budget, appoint department heads, and control most City operations. City Council (the legislative branch) can only react and make amendments to the Mayor’s proposed budget; it does not have the ability to introduce its own alternative budget.

This imbalance is not inevitable. Both Los Angeles and New York City demonstrate how charters can codify a clear separation of powers and limit this type of executive dominance. For example, Los Angeles’ city charter facilitates an extensive veto process by which City Council can amend the Mayor’s budget.

Additionally, the Mayor appoints committee chairs in the City Council. This means that the Council committees charged with evaluating the budget – the Committee on Budget and Government Operations and the Committee on Finance – are generally helmed by alders friendly to the Mayor. Given the large size of Chicago’s City Council, committees are an essential part of the legislative process. Neither of Chicago’s peer cities allow the executive branch to exercise appointment power over leadership of the legislative branch. In fact, New York City allows council members to select a budget negotiating team to negotiate directly with the Mayor. In short, a city charter could provide the Council with more autonomy by removing mayoral appointment, creating a budget negotiating team, defining a budget amendment and veto process, and allowing Council members to introduce alternative budgets.

2. Enable Analysis and Oversight from the City Council

In Chicago, the Mayor’s office plays the lead role in financial management and oversight. The Mayor appoints all three key financial leadership positions: the Chief Financial Officer, Budget Director, and Comptroller. This means that the executive office controls what financial information is released to City Council members and the public. City Council lacks an empowered fiscal oversight arm to vet the Mayor’s projections and fiscal policy changes.

In 2015, the Chicago City Council created the Council Office of Financial Analysis (COFA) to serve as the independent analysis office providing research on the budget and other finance issues to the Council. However, COFA remains significantly under-resourced, with the most recent City budget providing for only five staff members. Without a strong COFA, City Council effectively remains dependent on the Mayor’s Office for fiscal information, reinforcing a cycle of executive control and legislative passivity.

New York City, in contrast, has multiple independent entities that provide budget analysis to the City Council and to voters, including its Independent Budget Office, elected Comptroller, City Council finance team, State Comptroller, and Financial Control Board.

It should be noted that recent reforms in Chicago’s 2025 Management Ordinance now grant COFA access to departmental budgeting software. However, COFA still does not have access to the budget work done by the City’s Office of Budget and Management (OBM) as the planning stages of the budget process unfold. To be truly effective, COFA needs regular updates on budget planning from OBM, as well as early embargoed access to the Mayor’s proposed budget so that it can conduct its analysis before Council members see the budget and begin hearings.

To compound the above challenges, Chicago currently has an incredibly rapid budget approval timeline, with a maximum of three months between the introduction of the Mayor’s proposed budget and the end of the fiscal year. Because of the compressed timeframe between the Mayor’s budget release and the City Council’s deadline for budget adoption, there is not enough time for Council members to fully vet and evaluate the proposal, hold meaningful budget hearings, obtain answers to questions from departments, suggest amendments, and evaluate the long-term financial impacts of budget decisions. Historically, this process has led the Council to grant a procedural stamp of approval rather than engage in substantive debate on fiscal priorities. In contrast, New York City’s charter codifies a five-month budget season.

In short, due to the short budget process and the lack of information and resources available to COFA, Chicago’s alders are functionally reliant on the Mayor’s staff for budget and financial information. A city charter could flip the script by codifying a budget timeline and funding for robust independent analysis and thereby empowering the Council to understand the budget on its own terms and respond to the Mayor’s proposals.

3. Strengthen Year-Round Budget Monitoring

Although city budgets get the most political attention at the end of the fiscal year, budgeting should be a year-round process. Chicago does have several requirements in place that help track operational spending and revenues throughout the year, including monthly and quarterly reports, as well as the newly enacted Mid-Year Budget Report. The Mayor’s Office additionally releases a three-year budget forecast around late August. However, the monthly reports only include updates to revenue, and neither report is discussed at public-facing meetings, so it is unclear how these are used to make budget adjustments throughout the fiscal year. Mid-year adjustments are often managed administratively by the Mayor’s team with minimal City Council involvement. Increased formal communication between the Mayor’s budget office and the City Council would help the Council and the general public remain informed about the main drivers of revenue and expenditure changes throughout the year, enabling them to make adjustments collaboratively.

This year, the City Council began holding mid-year budget hearings, prompted by the release of the Mid-Year Budget Report from the budget office. However, these hearings did not begin until September 2025, only one month ahead of the Mayor’s expected budget release and far too late to have a meaningful impact. Moving forward, there is an opportunity for City Council members to better utilize these hearings by holding them earlier in the year and using them as an opportunity to discuss budget adjustments that must be made to ensure a balanced budget by the end of the year.

Turning again to our peer cities, both have their budget monitoring codified in their charters. New York City updates its financial plan four times a year and requires regular reporting on key items such as the 10-year capital strategy and annual debt reports. Los Angeles issues quarterly financial status reports, which the City Council uses to make mid-year adjustments.

A city charter in Chicago could address requirements for budget monitoring throughout the year and how reports are to be used, potentially through formal City Council hearings.

4. Require Long-Term Operational and Capital Planning

Chicago operates on a one-year budget cycle, which often results in financial decisions focused on short-term solutions rather than sustainable fiscal strategies. While the City produces a three-year Budget Forecast each year, it does not address strategies to achieve long-term structural balance and close budget gaps. It also lacks requirements for identifying risks, evaluating recurring costs, or explaining how future challenges, such as economic downturns, demographic changes, and policy shifts, will be managed.

In addition to the short-term focus of financial and budget planning, Chicago’s approach to comprehensive capital planning is also fragmented. The City’s capital plan is produced separately from the annual budget and lacks a systematic process for determining the financial impacts of capital projects, which projects should take priority, how projects should be funded, and how investments align with broader fiscal and economic goals. While Chicago does have a five-year Capital Improvement Plan, it lacks a needs-based evaluation of long-term infrastructure priorities, and it is not tied to the City’s operating budget.

Another aspect of the problem is that a large amount of infrastructure spending is tied to hyper-local projects that are not part of a central capital budget. For instance, the Aldermanic Menu Program allocates $1.5 million annually to each of the 50 City Council members to use for capital projects within their ward. Additionally, tax increment financing (TIF) districts divert a share of property taxes for economic development within specific areas. Much of this capital spending is allocated on a case-by-case basis, based on which developers apply for funding and their political support from elected officials. While these programs provide flexibility for addressing community-specific needs, they lack transparency, strategic oversight, and equitable resource distribution, leading to disparities in infrastructure investments across neighborhoods.

Chicago’s current approach stands in stark contrast to the structured, charter-based long-term planning used by its peer cities. New York City demonstrates how long-term operational and capital planning can be codified within a city charter. NYC’s charter lays out long-term planning requirements, including a four-year financial plan that gets updated annually in the budget and revisited quarterly. These requirements make long-term thinking a structural obligation rather than an administrative preference.

A city charter could require that Chicago follow best practices for long-term financial planning, ensuring that fiscal sustainability and transparency are built into the structure. Specifically, a charter could require:

- A five-year projection of revenues and expenditures, fund balance trends, reserves, and cash flow projections.

- Projections that incorporate future debt issuances and long-term liabilities.

- A discussion of how the City will mitigate risk based on internal and external factors such as economic downturns, demographic changes, and policy shifts.

Instead of simply providing projections of revenue and expenditure changes, the long-term financial planning process would ideally also include a description of financial policies and goals, a scorecard of financial indicators, possible strategies to address financial imbalances, and a process for incorporating public input.

In addition to operational planning, a charter could strengthen long-term capital planning by integrating it into the budget cycle. It could require that the capital plan include information such as planned debt issuances, so that future bonds can be incorporated into current debt schedules and projections. A charter could also require a needs-based evaluation of projects to ensure that programs like the Aldermanic Menu operate under clear guidelines. This would help to bring Chicago in line with peers like New York City, which requires a ten-year comprehensive capital strategy and ongoing reporting on debt and obligations.

By embedding these requirements into a charter, Chicago would move from a short-term, fragmented approach to one that is structured, transparent, and financially sustainable. Strengthening the City’s long-term planning framework would allow better coordination of infrastructure investments, clearer assessment of life-cycle costs, and assurance that funding mechanisms support long-term fiscal health.

Conclusion

It is clear that Chicago’s budget process must be improved. A city charter is one clear solution. Without comprehensive guidelines and requirements, Chicago’s budgeting process will remain vulnerable to the priorities and personalities of whoever holds executive office. In our current system, each administration redefines the rules, leaving no enduring structure to ensure long-term fiscal stability or public accountability. A charter would create permanent guardrails that outlast political cycles and a framework that Chicago’s residents, businesses, and civic institutions can rely on to protect the City’s financial integrity.

Appendix: How Chicago Compares to Charter Cities

The following table summarizes key differences between Chicago’s current structure and the charter-defined governance systems of Los Angeles and New York City. While no city’s model is perfect, both peers demonstrate how codified roles, timelines, and transparency requirements can yield more accountable and balanced budgeting processes.

This research was supported in part by the DeBlasio Family Foundation. The Civic Federation is a nonpartisan, independent research organization, and the views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the DeBlasio Family Foundation.