September 16, 2022

With the increasingly polarized political environment and the November 2022 mid-term election approaching, the debate about pretrial reforms in Illinois has been at the forefront in the news media and on social media. The pretrial reforms, referred to as the Pretrial Fairness Act, were passed via Public Act 101-0652, known as the SAFE-T Act (Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today). Much of the information being circulated and even promoted by some government bodies has been inaccurate. Given the current heated partisan rhetoric, this blog post aims to clear up misconceptions and inaccurate claims from the Civic Federation’s objective, nonpartisan standpoint, and explain some of the key pretrial provisions included in the SAFE-T Act. For the Civic Federation’s summary of the provisions of the bill, see this blog post.

First, what the SAFE-T Act does not do:

Claims that the new law allows for the automatic release of people charged with serious, violent felonies are misleading. There have been numerous claims that the SAFE-T Act will result in the release of people charged with serious crimes such as aggravated battery, robbery and burglary. Based on the criteria laid out in the statute, many violent felonies will be eligible for detention (see below for more about charges eligible for detention) and judges will have discretion to consider the defendant’s risk to public safety and risk of willful flight to avoid prosecution in their all pretrial release decisions. Detention eligibility will in many cases depend on the severity of the charge and individual circumstances of the case.

The law does not prohibit police officers from arresting and removing criminal trespassers from private property if the person poses a threat to the community, any person, or their own safety. Police officers will continue to be able to use their discretion about what constitutes a public safety risk in these instances. For example, see this flow chart for guidance on citation procedures.

The SAFE-T Act does not prohibit law enforcement from acting when someone released on electronic monitoring violates the terms of their release, which can mean the person failed to appear at a court hearing or went outside of a boundary set based on a location monitoring device. The law does add a new time requirement that in order to be guilty of an escape or violation of a condition of an electronic monitoring, the person must remain in violation for at least 48 hours. However, this does not change the ability of law enforcement or pretrial services programs to investigate and/or rectify the violation.

It is also important to remember that the pretrial release changes in the SAFE-T Act have not yet taken effect; they go into effect on January 1, 2023. Attributing an increase in crime to the SAFE-T Act is unfounded given that the pretrial provisions not yet gone into effect.

What does the SAFE-T Act do?

The pretrial provisions within the SAFE-T Act, known collectively as the Pretrial Fairness Act, take effect on January 1, 2023. These pretrial provisions include the following major changes:

Elimination of cash bail:

Beginning January 1, 2023 judges will no longer be able to require people arrested and charged with crimes to pay money for their pretrial release. This means that the current system, in which access to cash often determines whether someone is detained in jail until trial, will be replaced with a system designed to detain people charged with more serious, violent crimes and to release people charged with non-violent, less serious crimes.

Changes to the pretrial release process:

Under the current pretrial system in Illinois, after a person is arrested they are brought before a judge for a bond hearing where the judge makes an initial decision about whether the person may be released from custody or held in jail. Judges determine whether to release the defendant, either without posting money (often called release on recognizance) or with the payment of a monetary bond, or to hold the person in jail without release. All defendants released are required to abide by general conditions of release including attending all required court appearances and not committing any new offenses. The judge may also order special conditions such as pretrial supervision (check-ins with a pretrial officer), electronic monitoring, drug testing and no contact orders.

Under the current Illinois bail statute, all defendants are eligible for bail before conviction, except where the proof is evident or the presumption is great that the defendant is guilty of certain offenses, including: offenses that carry a maximum sentence of life imprisonment; offenses where the minimum sentence includes imprisonment without parole; stalking; illegal gun possession in a school; or making a terrorist threat. When considering the amount of monetary bail and conditions of release, the law requires judges to consider more than 30 factors relating to the nature of the charges, the defendant’s criminal history, prior instances of failure to appear and the defendant’s home and community information. The law directs judges to require upfront payments only when no other conditions of release will reasonably ensure that defendants will appear for future court dates and not pose a public safety risk. It also states that any cash bail should be “not oppressive” and “considerate of the financial ability of the accused.” The existing law also already includes a presumption that any conditions of release imposed shall be non-monetary in nature and the least restrictive conditions necessary to ensure appearance of the defendant in court.

Beginning in January 2023, requiring the payment of money for release will no longer be a factor in pretrial release. Rather, defendants will either be released (with any special conditions imposed by the judge) or held in jail. There will continue to be a presumption of release, except when a person is charged with offenses eligible for detention or has a high likelihood of willful flight.

Any person arrested and taken into custody will appear before a judge for an initial hearing. When setting conditions of release, judges must consider the nature and circumstances of the offense charged, the weight of the evidence against the defendant, the defendant’s history and characteristics and the risks that would be posed by the defendant's release. The court may use a risk assessment tool to aid in determination of appropriate conditions of release. Judges will continue to be able to set the same conditions laid out in existing statute. The Pretrial Fairness Act also requires the defendant to be appointed a public defender or other legal representation prior to their first appearance in court.

If the person is charged with a detention-eligible offense, the State’s Attorney can file a petition for a detention hearing. This will trigger a detention hearing,[1] at which the judge will make determination on whether to detain or release the defendant.

Charges eligible for pretrial detention:

In cases where the State’s Attorney files a petition for a detention hearing, the court will hold a detention hearing to determine whether to release or detain the defendant. The court may deny pretrial release based on any of the following criteria:

- Public Safety Risk:

- The defendant is charged with a forcible felony for which a sentence of imprisonment without probation, periodic imprisonment or conditional discharge is required upon conviction (i.e., not eligible for probation), and the defendant's release poses a specific, real and present threat to any person or the community. For a list of non-probationable offenses, see this list compiled by the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council and an accompanying explanations and limitations document. Non-probationable forcible felonies include charges such as murder, second degree murder, aggravated battery, residential burglary and vehicular hijacking, among many other offenses. It is important to note that eligibility for detention in some cases will depend on the specific circumstances of the current charge, as well as the person’s criminal history;

- The defendant is charged with stalking or aggravated stalking and the defendant's release poses a real and present threat to the physical safety of a victim of the alleged offense;

- The defendant is charged with domestic battery or aggravated domestic battery and the defendant's release poses a real and present threat to the physical safety of any person;

- The defendant is charged with a sex offense (excluding public indecency, adultery, fornication and bigamy) and it is alleged that the defendant's pretrial release poses a real and present threat to the physical safety of any person;

- The defendant is charged with certain weapons-related violations[2] and the defendant's release poses a real and present threat to the physical safety of any specifically identifiable person(s); or

- Flight Risk:

- The defendant is charged with any of the above felonies or any felony other than a Class 4 felony (this includes murder, Class X, 1, 2 or 3 felonies) and is found to have a high likelihood of willful flight to avoid prosecution.

The Loyola University of Chicago Center for Criminal Justice has found that there are approximately 400 specific statute references for potentially detainable offenses based on the above public safety risk criteria.

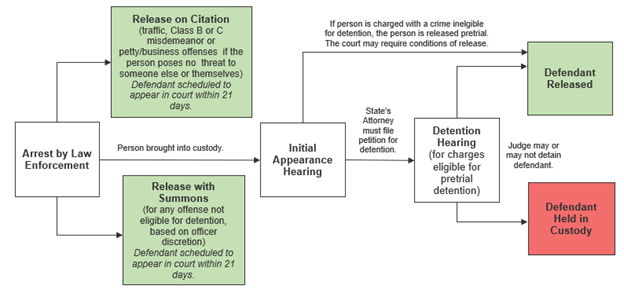

Release from police custody for certain offenses: The Pretrial Fairness Act creates new provisions for police officers to release people arrested for certain crimes from their custody rather than appearing before a judge.

- Citation in lieu of custodial arrest: This provision requires law enforcement to issue a citation in lieu of custodial arrest for traffic offenses, Class B and C misdemeanor offenses or petty and business offenses in which the person poses no obvious threat to the community or another person and who have no medical or mental health issues that pose a risk to their own safety. Those released on citation must be scheduled into court within 21 days. The law enforcement officer may still use their discretion to determine whether the person poses a threat, and if so, the law enforcement officer can take the person into custody for an initial appearance before a judge.

- Release with a summons: This provision allows law enforcement officers to release a person arrested for an offense for which pretrial release may not be denied without appearing before a judge, with a summons to appear in court within 21 days. The law enforcement officer may use their discretion to determine whether to release the person with a summons, with a presumption in favor of release.

The following flow chart shows a simplified version of the steps in the revised pretrial process from the point of arrest to either release or detention.

More detailed flow charts created by the Illinois Supreme Court Pretrial Implementation Task Force with considerations for each step in the pretrial process can be found at this website.

What is Illinois doing to prepare for reforms?

The Illinois Supreme Court created a Pretrial Practices Implementation Task Force in 2020, which was initially tasked with implementing recommendations made in the final report of the Commission on Pretrial Practices released in April 2020. After passage of the Pretrial Fairness Act as part of the SAFE-T Act in early 2021, the Task Force shifted its work to provide implementation guidance to circuit courts and other county criminal justice system stakeholders, as well as Illinois lawmakers, in order to successfully implement the Pretrial Fairness Act provisions of the SAFE-T Act. Since that time, the Task Force has formed several subcommittees and established three pilot sites for preliminary implementation. The Illinois Supreme Court also established an Office of Statewide Pretrial Services to ensure that all counties throughout Illinois have a pretrial services program to conduct risk assessments and monitor defendants released pretrial.

As part of the Task Force’s preparations for the new pretrial system, it has been producing a series of flowcharts and implementation considerations, as well as hosting monthly public town halls in order to educate system stakeholders and members of the public on various aspects of the Pretrial Fairness Act. For more information, see the Illinois Supreme Court Pretrial Implementation Task Force website.

In addition to the statewide Task Force, counties around the State of Illinois are also working on their own preparations. Cook County, for example, has convened working groups to determine what structural changes, policy changes and funding changes need to be made ahead of the SAFE-T Act’s effective date.

What impact might the new law have on pretrial detention?

Loyola University researchers have begun to estimate the potential impact that the new pretrial detention standards will have on the number of people detained and released throughout Illinois. The Loyola University Center for Criminal Justice examined arrests between 2017 and 2021 to see how many of those would be eligible for detention under the Pretrial Fairness Act. The study found that in the two-year period from 2020-2021, 44% of all arrests in Illinois were for charges potentially detainable pursuant to the Pretrial Fairness Act. Of those, 27% were for charges detainable under the public safety standard (a total of approximately 45,000 arrests) and 17% were potentially detainable under the willful flight. The remaining 56% of arrests were for offenses that will be ineligible for detention. Among the detainable offenses under the public safety standard, the majority, 70%, were for domestic violence offenses or violations of an order of protection.

However, the report notes that not all of these potentially detainable arrests will automatically qualify for detention because risk to public safety and flight risk must be taken into consideration in judges’ release decisions. The analysis estimates that as few as 15,500 or as many as 70,000 individuals in Illinois could be detained once the PFA takes effect.

See the Center’s data tool on arrests eligible for detention to examine the number of detainable offenses and filter by each judicial circuit in Illinois.

Related Links:

Summary of Provisions in Illinois House Bill 3653: Criminal Justice Omnibus Bill

Pretrial Reform Efforts in Illinois and Outcomes from Other States

What the Data Tell us about Bail Reform and Crime in Cook County

Elimination of Cash Bail in Illinois: Financial Impact Analysis

What We Learned about Bail Reform and Police Budgeting Reform from Two Expert Panel Discussions

[1] The detention hearing must be held either immediately, or if a continuance is requested, within 48 hours of the initial appearance if the defendant is charged with a Class X, Class 1, Class 2, or Class 3 felony, and within 24 hours if the defendant is charged with a Class 4 or misdemeanor offense. 725 ILCS 5/110-6.1.

[2] The violations specified in this section include the following offenses: aggravated discharge of a firearm; aggravated discharge of a machine gun or a firearm equipped with a device designed or use for silencing the report of a firearm; reckless discharge of a firearm; armed habitual criminal; manufacture, sale or transfer of bullets or shells represented to be armor piercing bullets, dragon's breath shotgun shells, bolo shells or flechette shells; unlawful sale or delivery of firearms; unlawful sale or delivery of firearms on the premises of any school; unlawful sale of firearms by liquor license; unlawful purchase of a firearm; gunrunning; firearms trafficking; involuntary servitude; involuntary sexual servitude of a minor; trafficking in persons; unlawful use or possession of weapons by felons or persons in the custody of the Department of Corrections facilities; aggravated unlawful use of a weapon; and aggravated possession of a stolen firearm.