May 23, 2019

Governor J.B. Pritzker’s FY2020 budget features an array of revenue-raising proposals, such as recreational cannabis and sports betting, that have attracted considerable attention. Another idea is less flashy but just as important to next year’s budget: a tax on health insurance plans.

As outlined by the Governor, the tax on managed care organizations (MCOs) would generate $390 million to be used in place of general operating funds to pay for State Medicaid costs. The tax would also result in an additional $1.2 billion of Medicaid spending, thanks to federal reimbursements. Most of that money would be used to pay back the taxes provided by MCOs that participate in the Medicaid program.

The numbers might have changed since the budget was released in February, but new details have not been made available to the public. The proposal is being ironed out by a Medicaid working group consisting of legislative leaders and Pritzker administration officials. The MCO tax could be part of a wide-ranging Medicaid bill that will be filed before the end of the General Assembly’s spring session on May 31.

Regardless of the final details, the new tax would follow the general pattern of other healthcare provider taxes, including Illinois’ longstanding hospital assessment program. Provider taxes, used in every state except Alaska, are a way to pull in more federal funds for Medicaid at no cost to the state.

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that provides healthcare coverage for low income individuals. Financing the program is a shared responsibility, with states receiving federal matching funds for eligible state expenditures. For most of the 3.1 million Medicaid beneficiaries in Illinois, the federal matching rate is currently 50.31%, which means that the federal government pays just over half the cost. In other words, for every dollar spent by the State, the federal government spends about $1.01. Reimbursement rates are higher for adults who became eligible for Medicaid due to the Affordable Care Act and for the recipients in the Children’s Health Insurance Program for families with higher incomes. Those rates are currently 93% and 88.22%, respectively.

Federal law allows a portion of the state share of Medicaid costs to be paid by healthcare providers, with certain limitations. In the case of Governor Pritzker’s proposed MCO tax, health insurance plans would be assessed a total of about $867 million per year, which would be deposited in a special Medicaid account. Of that amount, $390 million would be used to cover Medicaid costs now paid from General Funds.

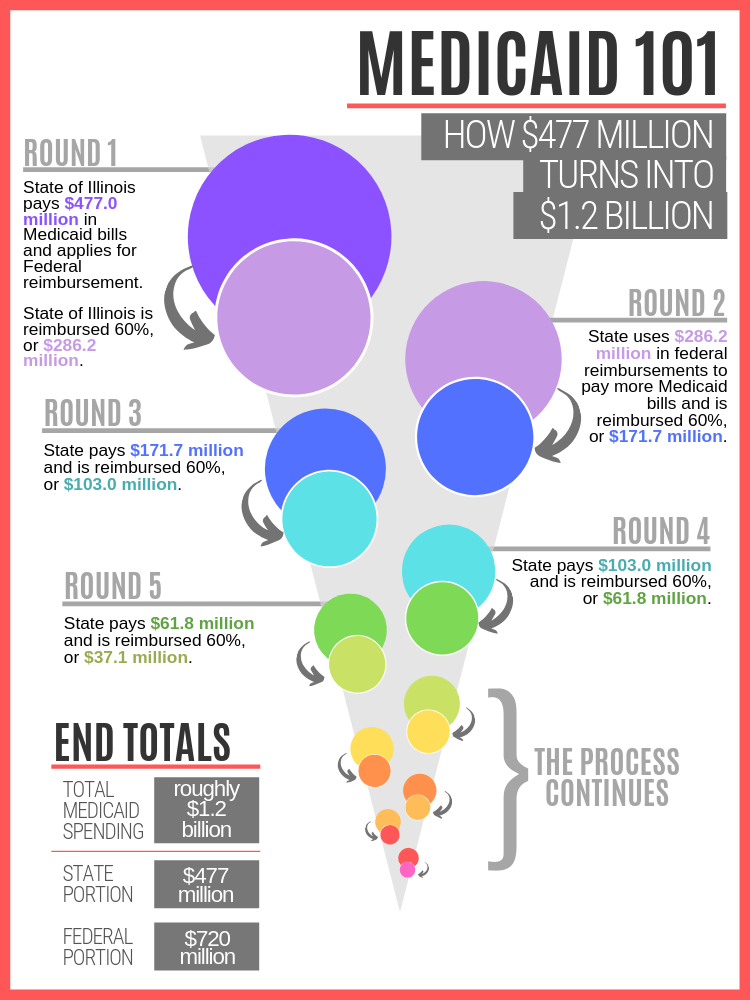

The remaining $477 million, when matched by the federal government at an estimated average rate of about 60%, would generate a total of approximately $1.2 billion. Most of this amount would go back to Medicaid MCOs to cover their additional tax expenditures, according to State officials, while the remaining $300 million to $400 million would be used for new Medicaid spending.

The diagram below shows how the $477 million results in $1.2 billion of funding through a cycle of spending and reimbursement that is referred to as “churning” by Medicaid finance experts. The cycle starts when the State spends $477 million on allowable Medicaid expenses and receives a 60% reimbursement, or $286.2 million, from the federal government. This process is repeated until Medicaid spending totals about $1.2 billion: approximately 40% from the MCO tax and 60% from federal reimbursements. This is a simplified version of the actual process because in practice all of the $477 million would not be collected or spent at one time.

To limit federal Medicaid costs, provider taxes must meet certain requirements, including that the assessments be broad-based across an entire group of healthcare providers and that each healthcare entity not be held harmless or guaranteed reimbursement for its tax payments. In the case of MCO taxes, the rules now require that they apply to both Medicaid and non-Medicaid MCOs. This requirement has not been popular among health insurers in other states who do not participate in the Medicaid program because they pay taxes but receive no benefits.

However, the Obama administration in 2016 approved MCO tax programs in California and Ohio with tiered rate structures that apply much lower rates to non-Medicaid health insurance plans than to Medicaid plans. In California, for example, the tax rates are based on the number of Medicaid and non-Medicaid enrollees. The tax is $45 per Medicaid enrollee month for plans with up to 2 million member months, compared with $8.50 per non-Medicaid enrollee month in similar sized plans. California lowered other taxes paid by some MCOs as part of its MCO tax package.

Until recently, it was not clear whether the Trump administration would agree to this kind of MCO tax. It was considered a positive sign when the federal government in December 2018 approved an MCO tax in Michigan that was similar to the tax in California. In an unexpected development, California Governor Gavin Newsom’s FY2020 budget did not include a proposal to extend that state’s MCO tax, which provides a net benefit of $1.5 billion for California’s General Fund and is set to expire at the end of June. Governor Newsom said he was concerned that applying to renew the MCO tax could hurt prospects for federal approval of other Medicaid-related requests.

Illinois’ tax on health insurers would be modeled after the taxes in California and Ohio, according to Governor Pritzker’s budget. Among the many remaining budget issues to be decided by the end of next week, the MCO tax is still in the mix.