April 01, 2021

Vehicular hijacking, commonly referred to as carjacking, has become a point of great concern among City and State officials due to an increase in incidents since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in carjackings follows a national trend, although overall crime in Chicago and across the nation is down. This blog post looks at the numbers and what the experts say can be done about the issue.

Vehicular hijacking is defined by statute as the taking of a motor vehicle from a person or in the immediate presence of a person by the use of force or by threat of use of force. Aggravated vehicular hijacking is defined by statute as a vehicular hijacking in which any of the following factors occur:

- The person from whose immediate presence the vehicle is taken is 60 years of age or older or has a physical disability;

- A person under the age of 16 is a passenger in the vehicle;

- The person committing the vehicular hijacking is armed with a dangerous weapon;

- The person committing the vehicular hijacking is armed with a firearm; or

- The person committing the vehicular hijacking discharges a firearm; or

- The person committing the vehicular hijacking discharges a firearm that causes great bodily harm, permanent disability, disfigurement or death to another person.

Vehicular hijacking is a Class 1 felony and aggravated vehicular hijacking is a Class X felony, with varying sentencing terms based on the severity of the circumstances involved.

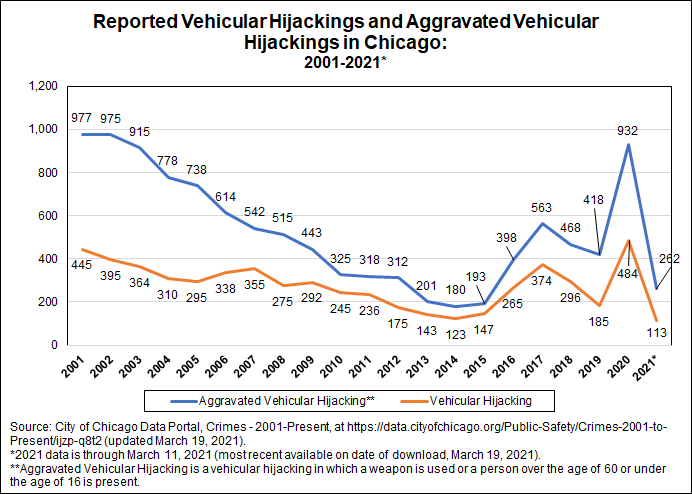

Vehicular hijackings in the City of Chicago increased in 2020 by 135% over the previous year, from 603 carjackings in 2019 to 1,416 in 2020. In 2021 there have already been double the number of carjackings reported during the same period the prior year. Between January 1 and March 11, 2021, there were 375 carjackings, compared with 161 carjackings during the same period in 2020, 91 carjackings during the same period in 2019 and 157 during the same period in 2018.

The following chart shows the number of vehicular hijackings and aggravated vehicular hijackings reported in the City of Chicago annually since 2001. The number of carjackings in 2001 was at about the level seen in 2020. Carjackings decreased gradually each year between 2001 and 2014, when carjackings hit their lowest level with a total of 303 carjackings (123 vehicular hijackings and 180 aggravated vehicular hijackings). Between 2014 and 2017, the number of carjackings rose significantly to a total of 937 incidents. The number of carjacking incidents then decreased in the following two years, before the dramatic increase experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and continuing into 2021.

The rise in carjackings is not unique to Chicago, as there have been increases in other cities across the U.S. including Minneapolis, New Orleans, Oakland, Washington D.C. and Louisville, Kentucky. Several factors have been identified as potential causes for the increase, including disenfranchisement associated with COVID-19, teenagers being disconnected from school and social service programs, precautions taken against holding juveniles in detention facilities, the anonymity associated with wearing masks and the difficulty with identifying suspects.

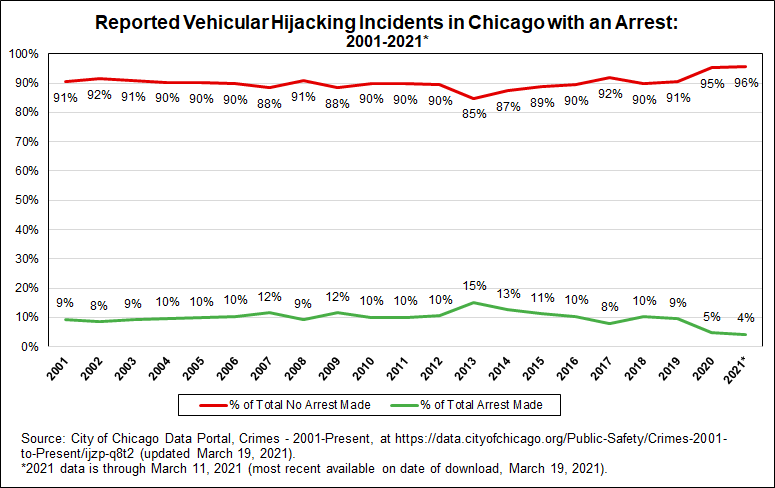

Carjacking incidents generally have a low rate of case resolution. In 2020, only 5% of vehicular hijacking incidents resulted in an arrest. Of a total of 1,416 carjackings in 2020, 62 of those incidents resulted in an arrest. That does not reflect the total number of individuals arrested, however. A total of 188 individuals were arrested in connection with the 62 carjacking cases in 2020, and of those 188 arrests made, 103 were youths (55%) and 85 were adults (45%) [1]. The following chart shows that the number of incidents resulting in an arrest has been historically low, never reaching higher than 15%.

While carjacking incidents have garnered much attention in the news, it is important to put them in context of other crime. Carjackings and other violent crimes including homicides and shooting incidents have increased over prior years, whereas overall crime has decreased. According to Chicago Police Department crime statistics, the number of murders reported from the beginning of this year through March 21 was 23% higher than the same period in 2020. Shooting incidents through March 21 of this year were 38% higher than the same period the prior year. However, reported incidents in other categories of crime including criminal sexual assault, robbery, aggravated battery, burglary and theft are all lower than in previous years. Crime data tracked by the Loyola University Center for Criminal Justice Research, Policy and Practice throughout the COVID-19 pandemic also shows that coronavirus containment policies have resulted in statistically significant reductions in drug crimes, criminal trespass, theft and battery offenses.

What is being done to address the increase in carjackings?

In response to the alarming increase in carjacking incidents during 2020, the City of Chicago Police Department expanded its carjacking task force in January, consisting of the Chicago Police, Cook County Sheriff, Illinois State Police, and federal law enforcement professionals who are working together to investigate and bring charges in vehicle hijacking incidents. The Police Department added 40 officers and four sergeants to investigate incidents, with a dedicated carjacking team in each of the city’s five detective areas. The Chicago Police Department also added a new section to its website on carjackings where members of the public can submit tips and evidence, learn about prevention and find news releases with information about arrests made.

At a Chicago City Council Public Safety Committee meeting held on January 22, 2021 to discuss carjackings, representatives from the Chicago Police Department and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office explained several things they are doing to improve prevention, incident response and investigations, including better information sharing among agencies and working to build strong cases in the absence of being able to identify suspects. They also explained the difficulties associated with apprehending carjacking suspects and meeting the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt that a defendant is the person who committed the crime. In some cases when evidence is insufficient, charges are reduced to a lesser crime such as possession of a stolen motor vehicle or criminal trespass to a vehicle. Those charges are much more common than vehicular hijacking, according to data presented by the Chicago Police Department during the meeting.

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx said at a February 1, 2021 meeting of law enforcement officials that her office brings charges in 90 percent of adult carjacking cases and 80 percent of juvenile cases, but that it is up to the court to determine the punishment and sentencing.

Some officials have been quick to blame juveniles for the increase in carjackings, and have suggested that penalties are not harsh enough to deter these violent crimes. Vehicular hijacking is a Class 1 felony, which carries a prison sentence of between four and 15 years for an adult. Aggravated vehicular hijacking, a Class X felony, carries a longer sentence term based on the severity of the case; an aggravated vehicular hijacking with a firearm, for example, requires that 15 years be added to the term of imprisonment in adult cases. For juveniles, sentences are governed by the Illinois Juvenile Court Act. The sentence for a juvenile carjacking ranges from five years of court probation to detention in the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice until the age of 21. The emphasis in juvenile court is rehabilitation rather than punishment. Juveniles charged with violent felonies including vehicular hijacking and aggravated vehicular hijacking are not eligible for diversion programs, whereas juveniles charged with less serious vehicle-related crimes such as possession of a stolen motor vehicle, could potentially be referred to a diversion program.

A panel of experts who testified at a Joint Senate Public Safety and Criminal Law Committee hearing on February 16, 2021[2] cautioned Illinois lawmakers against reflexively increasing penalties, arguing that the penalties for aggravated carjacking are already severe. Historically, they said, punitive policies have increased incarceration and have failed to reduce crime or improve public safety. They suggested that fear of punishment is not a deterrent, whereas fear of being caught by family members, community members or law enforcement is a deterrent to committing a crime.

Several solutions were offered by Stephanie Kollmann of the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law in a presentation at the February 16 Senate Committee meeting. These solutions include providing age-appropriate interventions, reducing the flow of illegal guns and increasing funding for violence reduction and prevention programs. Likewise, at the City Council’s January 22 Public Safety Committee meeting, Maryam Ahmad, Chief of the Juvenile Justice Bureau of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, spoke about the urgent need for more restorative services to address trauma and mental health.

Data Limitations

While some Chicago and Cook County criminal justice data is readily available through public datasets online, many data questions related to case outcomes, especially with regard to juveniles, are difficult to answer. The Chicago Police Department produces public datasets about reported crime incidents on the City of Chicago open data portal website, as well as some other statistics on the CPD website. The Cook County State’s Attorney also publishes public data sets on felony adult cases, including case initiation (charging information), disposition and sentencing decisions. The office also accepts requests for statistics through its website. Both agencies are subject to the Freedom of Information Act, meaning that they are required by law to provide responses to requests for information (while following exemptions and privacy protection requirements under the law).

Court data, however, is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. Requests for data can be submitted to the Cook County Chief Judge but responses are discretionary. Juvenile records are confidential and restricted under state law. These limitations on both publicly available data sets and the process for requesting court statistics make it difficult to obtain information such as:

- Court decisions in adult cases and the outcomes of those cases;

- The number of juveniles arrested and charged, and for what alleged crimes;

- Outcomes of juvenile cases including the number of cases that result in probation, detention, diversion programs, or no charges; and

- Information about juvenile probation and diversion programs run by the Cook County Circuit Court and the effectiveness of those programs.

The limitations of readily available data hinder the ability to look at the carjackings issue holistically, as was evident at the January 22 City Council Public Safety Committee meeting. For example, at the Chicago Police Department could not immediately provide responses to questions from aldermen including:

- How many carjacking arrests have had charges approved by the State’s Attorney’s Office?

- How many cases get dropped down from vehicular hijacking to criminal trespass of a vehicle or other lesser charges?

- How many of carjacker arrestees have a prior record?

- How many hijacked cars are recovered?

CPD and State’s Attorney representatives said they would need to follow up on those questions.

Another limitation is the way crimes are classified and categorized. Vehicular hijacking is a robbery offense. So in some data sets, carjacking numbers are included in a general robbery category, making it difficult to assess trends at a more granular level. There is no national data on carjackings because vehicular hijacking is classified as robbery by the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting, so carjackings are counted together with other all other robberies.

[1] Presentation by Stephanie Kollmann, Clinical Fellow and Policy Director of the Children and Family Justice Center at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, at an Illinois Senate Joint Public Safety and Criminal Law Committee subject matter hearing on public safety outcomes, February 16, 2021. A copy of the presentation is available at https://www.law.northwestern.edu/legalclinic/cfjc/documents/vhpresentationslides.pdf.

[2] The panel of speakers at the Senate hearing included Kathy Saltmarsh, Executive Director of the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Committee; Delrice Adams and Jessica Reichert of the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority; Ben Ruddell, Director of Criminal Justice Policy, ACLU of Illinois; Greg Jackson of the Community Justice Action Fund; and Stephanie Kollmann, Policy Director of the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law.